The Majesty and Mystery of Monarch Butterflies

Photo credit: Keith Krueger

by Linda Martinson

Blue Ridge Naturalist

I was walking recently with a seven-year-old friend while she collected caterpillars. She placed them on her arms and on the handlebar of her scooter and wondered how many legs they had. I mentioned to her that, hopefully, all of her caterpillars will turn into butterflies. She glanced at me skeptically and said, “I just can’t understand how that happens.”

The large insect order of Lepidoptera comprises both butterflies and moths, insects with four wings covered with minute, overlapping and often colorful scales. There are many more moths than butterflies in the order, about 89-94 percent moths to 6-11 percent butterflies, and their distinguishing characteristics are sometimes confusing. However, although both butterflies and moths are caterpillars in their larval stage of life

and many of them could be described as fuzzy, there are no fuzzy butterfly caterpillars, only smooth. So we could be confident that my young friend’s caterpillars, all smooth, would become butterflies if not eaten, stepped on or over-collected.

It is indeed a challenge to understand the amazing metamorphosis from egg to caterpillar (larva) to pupa (chrysalis for butterflies or cocoon for moths ) to adult butterfly or moth. And the metamorphosis of Monarch butterflies is especially complicated.

Photo credit:

monarch-butterfly.com

Photo credit: askabiologist.asu.edu/monarch-life-cycle

Monarch butterflies are colorful with distinctive wing patterns, and they are generally considered the most beautiful and majestic of butterflies. They also have some fascinating characteristics different from other species of butterflies. For example, they flap their wings at about a quarter of the speed of other butterflies. Monarchs fly slower and more majestically than other butterflies because they are poisonous to their predators such as birds, frogs and lizards. In their caterpillar larval stage, Monarchs eat and store a poison from their exclusive diet of milkweed leaves that makes them toxic to predators throughout their lifetime. Their striking color and markings advertise only beauty to us, but clearly broadcast “poisonous-do not eat” to potential Monarch predators.

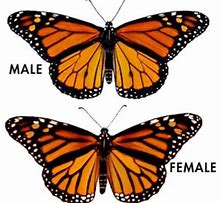

Can you tell if these are male or female Monarchs? Read on…

Photo credits: Bing.com

Female monarchs have thick bold veins and males have two small patches on their wings.

Another strange and mysterious characteristic of Monarch butterflies is their life cycle. There are four unique annual stages in the life cycle of Monarchs that are completed by each of four generations of each butterfly, i.e., four separate Monarch butterfly descendants each go through four or five stages in one year.

During Stage 1, early in the year, Monarch butterflies locate a mate and then migrate north from Mexico to search for just the right milkweed plant upon which to lay their eggs. After about four days, the eggs hatch and the caterpillars begin eating milkweed leaves. A caterpillar can eat an complete milkweed leaf in just a few minutes, and they will gain about 2700 times their original weight in their short life span of about two weeks. Then each caterpillar will attach itself to a leaf or stem and begin the process of metamorphosis by transforming itself into a chrysalis. During the 10 days of the chrysalis phase, the caterpillar is going through an amazing change to an adult butterfly. The Monarch butterfly then flies around, feeding on flowers and finding a mate during its short life of only about two to six weeks.

During the next two to three months of the year, Stage 2, the new Monarch butterflies lay their eggs and each hatched larva eats, grows and metamorphoses into a chrysalis and then hatches into the second generation mature butterfly. It then lives out its short but colorful and free lifespan flitting around feeding on flowers and laying eggs.

During the summer months of the year, Stage 3 occurs: a third generation of Monarch butterflies lives through the same life-cycle as the first and second generations (i.e., mate, lay eggs, hatch into a caterpillar and eat voraciously, grow, change into a chrysalis and hatch into a butterfly).

The fourth and final generation of Monarch butterflies repeats the processes of metamorphosis: mating, laying eggs, hatching into a caterpillar, eating and growing, changing into a chrysalis and hatching into a mature butterfly with one additional and astonishing step, Stage 4.

The final generation of Monarch butterflies also migrates in the late summer hundreds of miles back to Central Mexico where they will hibernate and live for six to eight months (instead of just a few weeks) until they migrate back to the United States — certainly a fascinating life cycle.

At their winter sites in Central Mexico, millions of Monarchs roost for the winter in huge groups in the trees. Their intricate and precarious migration pattern has been given a “threatened phenomenon” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). In 1986, the Mexican government established 62 square miles of forests as a Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, and this area was further extended to 217 acres in 2000.

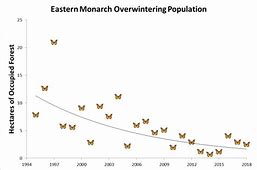

Monarchs in the United States have lost an estimated 165 million acres of breeding habitat due to development and herbicide spraying. Milkweed plants have been almost eradicated in several areas largely due to increased herbicide spraying, mostly on corn and soybean crops that have been genetically modified to tolerate direct herbicide spraying.

Monarch population graph courtesy Center for Biological Diversity.

Locally at Richland Ridge, there are several varieties of planted flowers and several native wildflowers growing on the POA property by the river that are nectar sources for mature butterflies including Monarchs. For example, there is a 150 yard stretch of beaver ponds, marshes and meadow with several wildflowers attractive to butterflies including Joe Pye weed, ironweed, asters, coreopsis, jewel weed, asters, Turk’s Cap lilies and Queen Anne’s lace. Butterfly weed and Swamp milkweed has also been planted and several Monarchs have been spotted every summer, so eventually we may be able to establish a multi-acre Monarch Way Station at Richland Ridge along the West Fork of the French Broad River.

Monarch butterflies on flowers at Richland Ridge Photo Credit:

Jan Foster

48 comments