Wildfires in Western North Carolina: How to Protect Our Homes, Property, and Communities

Blue Ridge Naturalist Network Nature Notes July 2017

by Linda Martinson Certified Blue Ridge Naturalist

It was smoky and scary in Western North Carolina last fall during a record-breaking wildfire season. Wildfires are uncontrolled/out-of-control blazes started naturally, by accident, or by arson. If the weather is dry and windy and there is plenty of fuel such as dry underbrush and fallen trees, wildfires can start easily, burn hot, and move fast —up to 14 miles/hour— creating ember showers and even higher winds and quickly consuming everything in front of them, including homes and people. Wildfires “crown”, i.e., they extend up to the treetops, and nearly alway have an extensive and severe negative environmental impact on soil, forests, plants, and wildlife, and destroying ecosystems and soil and plant biodiversity when large tracts are burned. When they burn human structures, wildfires not only can cause total physical destruction of property and death, they can create exceptionally toxic, even deadly, air pollution in surrounding areas.

Last summer and fall was an exceptionally dry period in WNC; the month between October 15 to November 15, 2016, was tied for the driest month in 65 years of record keeping. And the month of October 2016 was the fourth warmest October on record in the area. Ten counties in the region, including Transylvania and Buncombe Counties, were in an extreme drought by early fall, the second most severe drought rating, and five counties west of here were in an exceptional drought, the most severe rating. The U.S. Forest Service described last fall as the fifth-driest season in the past 104 years for Western North Carolina.

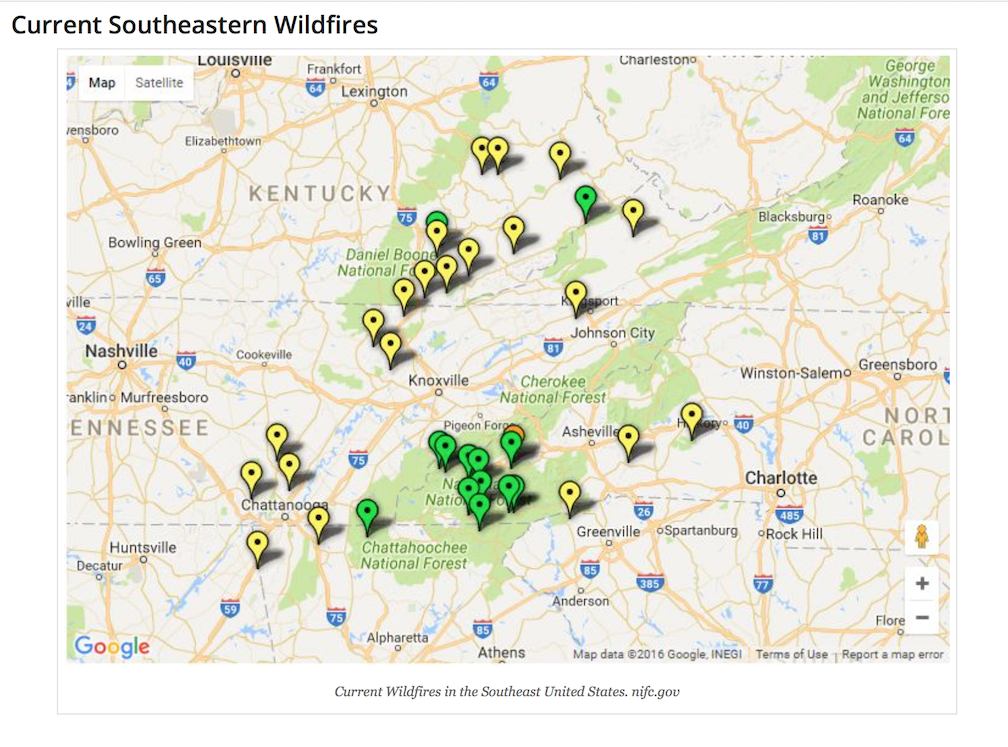

Because of these prolonged and exceptionally dry conditions, combined with unusually warm temperatures and frequent gusty and high winds, the number of wildfires in region increased dramatically. By mid-November 2016, there were 38 active fires in 8 Southeastern states that eventually burned 119,000 acres including 45,000 acres of national park land, and a state of emergency had been declared for 25 counties. The total cost of these wildfires was estimated to be between $40-50 million ($10 million in North Carolina alone), a cost that was higher than the totals spent for the past seven years combined

Then, on November 28, a fire began in the Chimney Tops area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park that rapidly broke into multiple fires that spread through the area in and around Gatlinburg, Tennessee forcing the immediate evacuation of 14,000 people. By December 4, the fires around Chimney Tops had burned 17,006 acres and destroyed over 2,400 structures. Fourteen people died, 191 others were injured, and damages in the area were estimated at over $500 million. Several nearby counties were placed under Code Orange or Code Red air quality alerts, the worst markers. It is estimated that 70% of all these fires in WNC were human-caused, mostly by intentional burning despite extensive fire bans, but around 50% of the fires were set deliberately by arsonists. Over 6,000 firefighters from 40+ states worked to contain these WNC wildfires.

Map from November 15, 2016 National Interagency Fire Center

Green posts are fires located in National forests & yellow posts on private land

Green posts are fires located in National forests & yellow posts on private land

Dollywood near Gatlinburg TN 11/20/2017 Photo: Bruce McCamish

Chilhowee Mountain in Tennessee 11/18/2017 Photo: USA Today

For many years, the average number of wildfires in the United States was about 100,000 per year, destroying about 4 to 5 million acres, mostly in the West. In recent years, there have been more fires all over the country burning up to 9 million acres or more every year. Because global climate changes are creating more frequent “micro-bursts” of very hot, dry periods alternating with very wet periods that create more underbrush which then dries out during dry spells, the Southeastern U.S. has become more flammable. Also, more people are moving south, and they often live in wooded areas. For example, more people live in the woods in North Carolina than in any other state, often in remote areas that are heavily forested with steep slopes (wildfires burn more quickly uphill) and with limited access by winding, narrow roads. Subdivisions near forests are becoming so common in the Southeast that they have their own distinctive description in forestry and fire protection terminology: Wildlife Urban Interfaces (WUI). Not only is it challenging to move heavy fire fighting equipment to these more remote and heavily forested locations, but also there is often not enough room to work, not enough local equipment and trained firefighters, and few or no easily accessible water sources. Also, seldom are all the homes in a WUI adequately adapted to be fire defensible.

The major lesson from the 2016 Southeastern wildfires is that we who live in Western North Carolina (whether it is in Transylvania County, the wettest county in NC or in Buncombe County, the driest, or in counties in between) must prepare to survive the inevitable future wildfires by starting with the premise, “Be afraid, be very afraid!” and then working to develop fire defensible homes and communities.

Steps for developing fire defensible spaces around both individual homes and communities located in a wooded or forested location.

Step One is to identify local and regional resources for assessing the fire risk hazard level of an individual home. Local forest rangers are the first resource to learn about home and property fire preparation and prevention. In Transylvania County, Andy Frank Rogers, the Transylvania County Ranger appointed by the N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services for the N.C. Forest Service, will come to your home to conduct an Individual Home Owner Assessment. This assessment is fast, easy, and effective; there are fifteen questions in four categories:

1. Size and clearance to the home entrance

2. Combustibility/heat resistance of the home

3. Drought resistance/combustibility of the landscaping around the home

4. Defensibility/combustibility of the perimeter of the home.

The answers to each question are scored from 0 up to 15 points and the score values range from Low Fire Risk Hazard 11 points or less; Low to Moderate Hazard, 12 to 30 points; Moderate to High Hazard, 31 to 81 points; to 82 to 125 points, High to Extreme Hazard.

Andy Frank Rogers, Transylvania County Forest Ranger, conducting a fire risk assessment.

Mr. Rogers encourages you to think of your house as if it were a potential campfire or burn pile and asking, how can it be defended from catching on fire and burning out of control? Are there a lot of dry leaves, plant debris, and other potential tinder around it? Is there a steady fuel source at the house such as wood shingles? Are there potential “ladder fuels” around the house such as shredded bark and other flammable mulch, several woody and waxy shrubs against the side of the house? Are there overhanging branches and flammable debris over or on the roof? How much fire defensible space is there around the house? Is it clear of firewood, gas tanks, and other flammable hazards? And finally, are the storage sheds and outbuildings equipped with a rake, shovel, ladder, and hose that are easily accessible?

He also asked several questions, for example, about the entrance and egress to our common property association land — do we have enough escape routes? Do we have a dry hydrant at the river or at some other close water source? Are there enough areas on the property where a fire engine could pull in, turn around, and exit easily? Are the road signs and home addresses marked with legible and reflective signs? Mr. Rogers spoke at our annual Property Owners Association meeting in mid-June and by the end of June, he had conducted two individual home fire risk assessments for our POA members with the goal of helping the owners of these homes both achieve a defensible fire protection perimeter and location with at least a low to moderate fire risk rating by making the recommended improvements.

Step Two is to begin thinking about not only defensible fire protection around your own home but also about developing fire defensible spaces around every home in your community. Think about it: there is an a significant advantage to make your own house fire defensible, but it is not a happy outcome if your house is standing alone in a larger area that is totally devastated by fire. It is far better to make sure that all of the homes your neighborhood/community are fire-adapted, i.e., able to survive a wildfire with the surrounding forests remaining largely intact and relatively unscathed as well as still biologically diverse with viable ecosystems.

Step Three: After your neighborhood/community is completely fire-adapted, the next step is to become a member of the Firewise Communities USA Recognition Program and work together with other fire adapted community groups to ensure that all the homes in the larger community area, as well as most of the forested area around it, become part of a regional fire defensible space. For example, after our Property Owners Association has completed the steps to becoming a fire adapted community group, we could then become a certified Firewise Community and reach out to other fire-adapted local communities to help plan and coordinate wildfire communication plans and internal safety zones within the area, to develop cooperative fire agreements and community protection plans, to develop and reinforce local codes and ordinances, and to develop and present local fire prevention and forest management education opportunities.

Jessica Hocz is the WNC resource contact for developing fire-adapted and Firewise communities. She is the Executive Director of the Mountain Valleys Resource Conservation and Development Council serving 8 counties in WNC. Mountain Valleys RC&D Council is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization established in 1974 to develop, improve, and conserve natural resources and to provide employment and other economic opportunities to the people of the four-county area of Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, and Transylvania Counties. In 1997 the Council expanded to include Cleveland, McDowell, Polk, and Rutherford Counties and to promote a team approach to wildfire education. Grants are available from the Council through the US Forest Service, because they believe that it is cheaper to prevent wildfires than to put them out.

The Mountain Valleys RC&D Council staff is also available for consultation. Ms. Hocz provided our Property Owners Association with a fire defensible checklist for homeowners, and discussed the collaboration among many local, State, and Federal agencies to support the Council. The five general steps toward obtaining Firewise Community certification are to:

1. Conduct a wildfire risk assessment for individual homes in the community

2. Form a community board or committee and create an action plan based on the

results of the home and property fire risk assessments in order to meet the qualifications to become a fire adapted community

3. Conduct a annual Firewise Day event such as joining forces to hire a chipper service to remove slash and dead branches from different locations on the property, to distribute Firewise wildfire emergency preparedness information to neighbors, or to staff an information booth at a local event such as the White Squirrel Festival in Transylvania County

4. Invest a modest amount of money per capita in local Firewise actions every year.

5. Submit an application to the state Firewise liaison for coordination at the State level.

There are huge advantages to developing fire-adapted communities in our local forested areas as well as to developing fully certified Firewise communities in even larger forested regions. For example, there are already two certified Firewise communities in Transylvania County which creates large fire defensible zones in two otherwise vulnerable parts of the county: around the Brevard Music Center and near a local camp. These larger Firewise Communities areas are obvious places for fire crews to go first to fight and contain wildfires because not only are the structures predictably fire defensible, the area already has well marked roads and home addresses, communication systems in place to help coordinate evacuation plans and other fire defensible strategies, and identified water sources and turn-around areas for firefighting equipment.

Another advantage to developing and promoting fire adapted and Firewise communities in Western North Carolina is the peace of mind that home owners have once they have secured not only their own homes as fire defensible but all the other homes in their local and regional communities. Perhaps the greatest advantage, however, is that these communities have made fire prevention and preparation plans that will help preserve the immensely valuable ecosystems and biodiversity of the forests and wildlife of Western North Carolina.

References: N.C. Forest Service and U.S. Forest Service and local news agencies

36 comments