Over the River and Through the Woods…and Past the Beaver Ponds, the Organic Garden, and the Meadow…to a Monarch Migration

October/November 2019

by Linda Martinson Blue Ridge Naturalist

Our place over the river and through the woods is Richland Ridge, a 500 acre development in Transylvania County, with about 70% of the property under conservation easement. From the road, nothing about Richland Ridge looks special or different. But as with many seemingly ordinary places in western North Carolina, the 120+ acres along the river at the entrance to Richland Ridge is special because it contains many unique and diverse natural communities and because, fortunately, this land has not been totally obscured by human activity.

Cross over the river on a bridge high above the West Fork of the French Broad River only about 8 miles from its headwaters. On your left is the part of the Richland Meadow Conservation Area that we call the front meadow. It is a meadow with native wildflowers and an organic garden, just past a riparian buffer area of river cane and other native riverside plants. Within the meadow and nearby are wetlands beaver impoundments at different stages of succession and a heritage farm site with remnants of land that had been cleared years ago, but that is now mostly being vigorously reclaimed by the forest.

Across the road from the front meadow, is a montane alluvial conservation area with a creek draining into the West Fork. This native community is found in sloughs or floodplain depressions in wetland forests that occasionally flood and that contain distinctive plants, insects and aquatic animals, sometimes rare. The montane alluvial area at Richland Ridge, for example, has a healthy population of spring peepers. The habitat of spring peepers in the U.S. has severely declined because of the loss of wetland areas across the country, and they are listed as endangered in two states. Montane alluvial communities once occupied as many as 1000 acres in the French Broad River basin, but is now reduced to less than 20 acres including our area at Richland Ridge.

The low-lying Richland Meadow Conservation Area is encircled by a big curve in the West Fork of the French Broad River. It was the site of a farm established in the 1940s and operated, in various ways, until the 1980s. The Jones family began to farm at Richland Ridge in February 1940, after Mr. Winfred Jones completed a stint with the Civilian Conservation Corps building the Blue Ridge Parkway. With his wife and nine children, he raised a variety of crops including sugar cane, corn, hay, sweet potatoes, strawberries, watermelon, and the cash crop of the time, burley tobacco. And until 1975,they worked the farm with no powered mechanical help. According to his son, Clyde, who was interviewed not long after Richland Ridge was placed under conservation easement, the farm was “all cultivated clear to the river”. “My father never even owned a car the whole time he lived here. We always had at least two teams of horses for work and one or two milk cows.” And for much of the time they farmed there, they also had no electricity or running water or indoor plumbing.

The Richland Creek Road bridge was not built until 1951/52, and before then the farm was accessed via a ford in the West Fork River near the entrance to the front meadow. To use this ford, the Jones family in their horse-drawn vehicle would have had to enter the river and travel about 100 feet in the riverbed before exiting onto dry ground. Sugar cane was the first crop they grew, but tobacco was their cash crop and it was likely planted in what is now the the front meadow, and it is also likely that at sometime they installed clay pipes under the field for drainage. There was a tobacco barn and several other outbuildings on the farm, but now there is only one building remaining.

Other historic uses of the Richland Ridge property include several periods of logging, grazing, installation of a small lake, mining for kaolin and construction of a rock quarry. All traces of these uses and abuses of the Richland Ridge native forests and natural features, just as with the Jones’s heritage farm, are now almost obliterated although you can find remnants of them as you hike around the property.

And long before these relatively recent enterprises at the Richland Ridge, the conservation sites by the West Fork were probably used by the Woodland and later the Cherokee Indians for farming and harvesting of river cane for basketry. As early as 2000 B.C., these Indians tended to live in semi permanent villages in stream and river valleys hunting and fishing, but also clearing fields and planting and harvesting crops like sunflowers, squash, beans, and maize.

In 1838, about 20,000 Cherokees were forced out of their homes in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee and moved west to Oklahoma by the U.S. military and various state militias. It is likely that any Cherokees in or near Richland Ridge were forced to leave then, too. However, they may have avoided the troops and joined the Oconaluftee Cherokee Indians, who were allowed to stay in WNC because of an 1819 treaty with the US government. Their descendants make up the Eastern Band of the Cherokee and now live in the Qualla Boundary reservation just south of Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

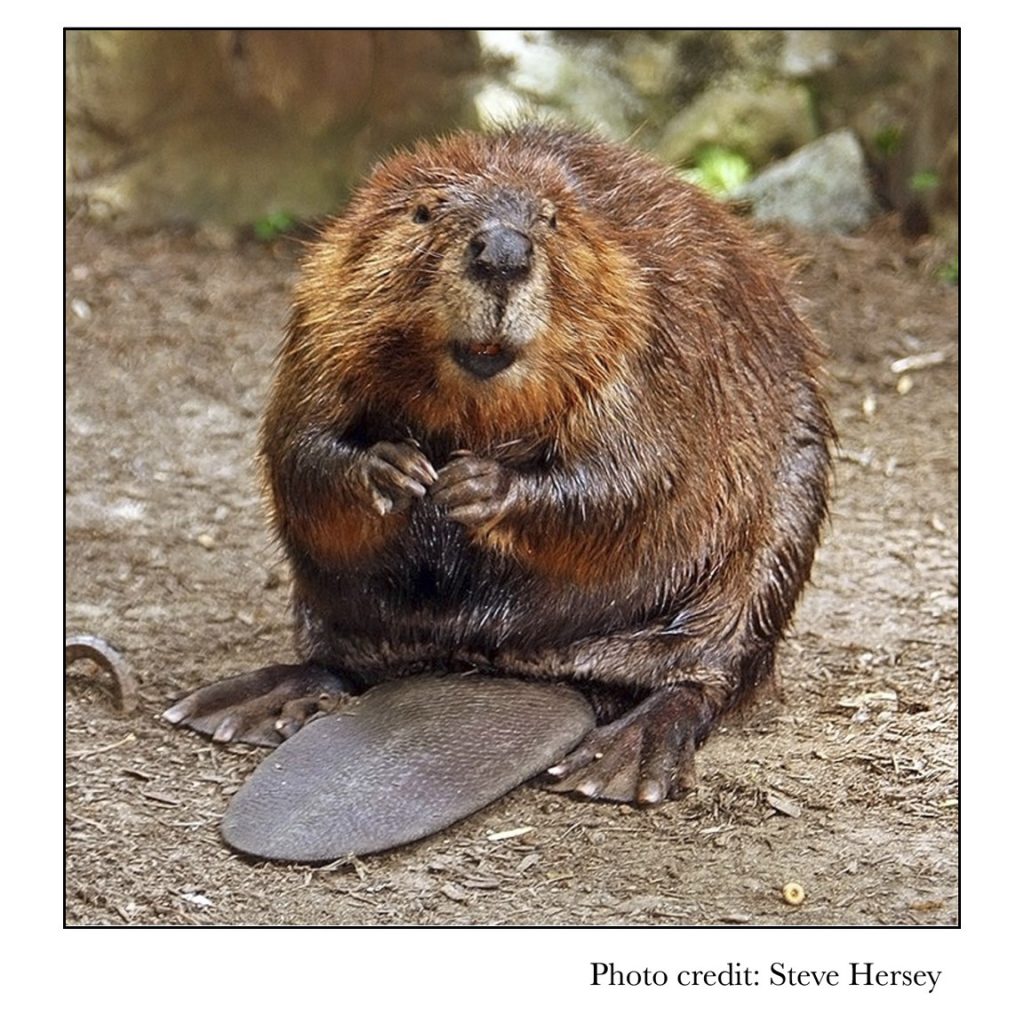

Even before the Cherokees had their land taken from them and were forced to leave, fur traders had begun to overkill beavers and by 1900 they had almost completely extirpated beavers in the United States. Also, wild turkeys, native trout and many other less noticeable species were also almost eliminated in this area by the early 1900s in various ways, and the many wetland areas were drained for farming. In the Blue Ridge Mountains, the effects of over-harvesting beavers and significant draining of wetlands were exacerbated, beginning at about the same time, by both the severe industrial logging that took place in Western North Carolina and Tennessee in the late 1800s/early decades of the 1900s and the loss of the American Chestnut trees to the blight beginning.

Severe logging on the mountainous areas, including at Richland Ridge, was followed by fire and floods, and it has taken decades to restore land, forests, and watershed areas in Western North Carolina—and it’s not done yet. Even though the land at Richland Ridge seems verdant and almost naturally wild, in many respects it is wounded land that is still healing. The land also is affected by more recent environmental threats for example, invasive species of plants; the hemlock woolly adelgid infestation of the native hemlock trees; and the threat of wildfires in dry seasons.

Fortunately, there have been and continue to be several efforts in Western North Carolina to restore, manage, and support our national forests and conservation areas with native species of plants, trees and animals. For example, many individuals in Western North Carolina took responsibility to reintroduce beavers, turkey and trout to restored areas in the 1960s and ‘70s, including the managers and rangers of the Great Smoky Mountains National park and the Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests. Now, we have fairly healthy populations of all these species throughout the Blue Ridge area, and many efforts and organizations have been established to sustain them.

If the old farm site at Richland Ridge had been acquired many years ago, and we had decided to restore this site to a vibrant montane riparian site with ponds and streams that stay full even during dry spells and with native vegetation, wildflowers, rare butterflies, legions of frogs, and non-toxic run-off into the French Broad River, could we have done it? Maybe, but it would have taken a lot of planning, cooperation, time, and money. However, the beavers that were re-established here, probably during the 1980s, have done it for free without any help from humans except for us leaving them alone and leaving the area undeveloped.

There are some increasingly rare wildflowers and other plants in the Richland Meadow Conservation area including native river cane, Turk’s Cap lily, ironweed, sedges and rushes, clematis, and Jack-in-the-Pulpit, English daisies, asters, goldenrods and marsh marigolds which have been enhanced by the monarch garden that has been established there with several milkweed plants. There are also several butterfly species in the area including monarchs (listed as endangered) and Diana fritillary (listed as threatened), as well as that healthy population of spring peepers. And I can now attest that, at least this year, we had a healthy population of monarch butterflies at the Richland meadow

A cold front swept south in early October this year and, according to the National Weather Service, monarchs as well as other butterflies, dragonflies and various other insects surfed the front by the thousands. Monarch butterflies migrate south for the winter for up to 3,000 miles to the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico, generally in late September/early October. In the Southeast, monarchs and blue asters seem to be “simpatico,” i.e., monarch migrations toward Mexico coincide with the peak of blue aster blooms. This year, I was fortunate to be in the middle of our front meadow with some neighbors on the first day of October watching hundreds of monarchs resting briefly during their long journey and sipping nectar from thousands of blue aster wildflowers. In 1996, the Eastern population of monarchs was estimated at about 700 million and now their population has dropped by more than 90%, so it was truly exciting and gratifying to see so many monarchs at Richland Ridge this year on their way to Mexico.

I am grateful for gracious and generous friends and neighbors; for wildflowers and wild places; and for monarch butterfly migrations. Happy Thanksgiving everybody!

References:

M. Forbes Boyle, Robert K. Peet, Thomas R. Wentworth, Michael P. Schafale, and Michael Lee. “Natural vegetation of the Carolinas: Classification and Description of Plant Communities of the Far Western Mountains of North Carolina.” University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. April 2011

Matthew Cappucci. “The Bugs Surfed the Front, Hitching a Ride on the Wind Shift.” Washington Post October 8, 2019.

Jennifer Frick, Chair of Math and Science at Brevard College. Personal discussion. October 2019.

Brad Kimzey. “Down at the Farm: Growing Up on Richland Creek.” November 11, 2003.

41 comments