Snakes are Up and At ‘Em

black snake photo credit: marylandzoo.com

by Linda Martinson

For several years, in early spring, a phoebe made her nest on a light fixture above the door of our second story screened-in porch. Eastern phoebes are flycatchers—insect eaters— of the genus Sayornis, a small group of medium-sized insect-eating birds. They are rather nondescript birds, grey with a darker head, plump and perky. They have short, thin beaks useful for catching insects and after they snatch an insect out of the air, they brag about it by bobbing their tails up and down and singing their song: “fee-bee…fee-bee”. They live year-round in the Southern Appalachians, and are happy to live near humans. They are also among the few predators that capture and eat bees.

Unlike most birds, phoebes reuse their nests, a cup of mud and moss padded with animal hair, year after year. And that’s what our phoebe was doing every spring, using the same nest above the door of our porch, until one fateful year. I heard a commotion early one spring morning…instead of singing its sweet phoebe song, our resident phoebe was scolding, almost screeching. A large black snake had slithered up all 16 porch steps and straight up the screen door and then curled itself around the nest on the light fixture, and it was slowly and deliberately devouring the phoebe’s eggs. All this without disturbing the nest! It was a sad but remarkable sight, and no phoebe ever nested there again.

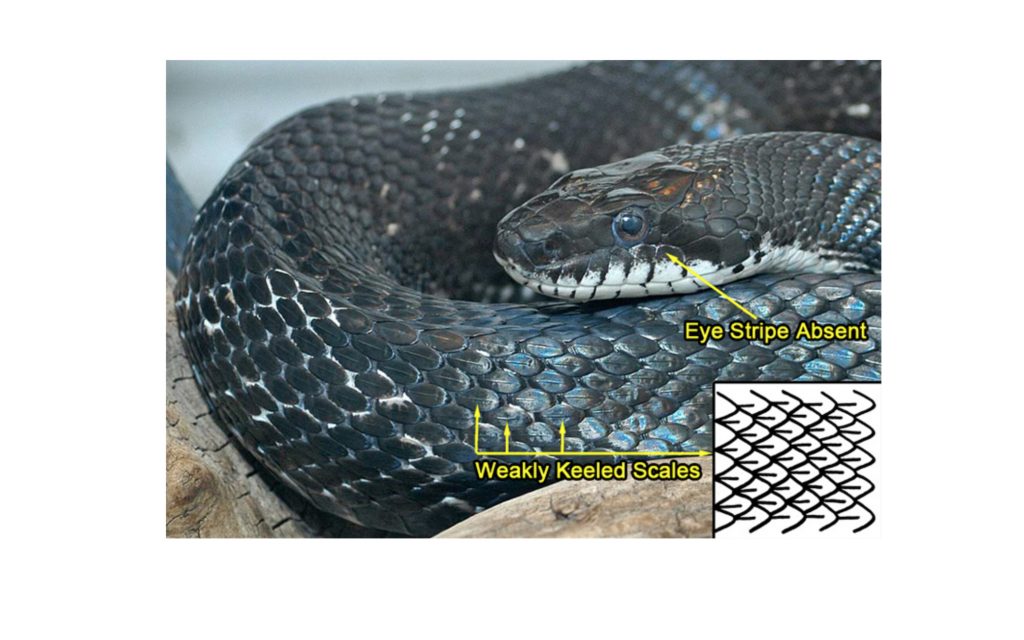

The snake that ate the phoebe eggs was an eastern rat snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) also called black rat snake, black snake, rat snake, pilot snake or chicken snake. They are rather docile and happy to live near humans and our mice, rats, chickens and eggs. Black rat snakes are considered the most common large snake seen in Western North Carolina as well as in many other parts of North Carolina. They range from New England to Georgia, as far west as northern Louisiana, and as far north as southern Wisconsin. Black rat snakes prefer to live in forests and grasslands, and a deciduous forest surrounded by grass near some houses is probably their ideal environment. This also describes the area where our houses at Richland Ridge are located. Black rat snakes are often seen because they are one of the few snakes that are diurnal, i.e., most active during the daylight hours.

In our mountains, black rat snakes are almost solid black, but they have variable color patterns in other parts of the state. Young black rat snakes are boldly patterned with dark blotches on a light gray background, and they have a dark diagonal eye stripe. As they mature, their blotches fade and they become more evenly darker colored and their distinct eye stripe fades. Black rat snakes are fairly heavy-bodied snakes with a whitish chin and usually a black and white checkered belly. Their bodies in cross section have been described as shaped like a loaf of bread rather than round.

The average length of adult black rat snakes is about 5 feet, but they can be as long as 8 feet, and four or five inches in diameter. They are excellent climbers because their scales are keeled rather than smooth. Keeled scales describe reptile scales that have a raised ridge down the center of their scales making them rough to the touch rather than smooth. Snake scales are dry and quite sensitive; each individual scale has the same sensitivity as the tips of our fingers. Black rat snakes are described as having weakly keeled scales because the ridges don’t extend the length of their scales. Garter snakes and water snakes also have keeled scales and they, too, are common snakes in Western North Carolina and at Richland Ridge.

Virginia Herpetological Society

All the snakes here at about 3,000 feet elevation are becoming more active as March gives way to April. Snakes don’t truly hibernate during the winter, instead they enter a cold- blooded state of extreme slowing down of their metabolism called brumation. Snakes sleep most of the time during brumation although sometimes they are awake, but very lethargic—almost in a torpor, and occasionally they go out to forage for food and water. Snakes in warmer climates stay awake all winter, but all the snakes native to North America brumate because of the relatively cold winters. For brumation, snakes seek out protected hiding places out of the wind, rain or snow such as dens used previously by other animals, caves, hollow tree stumps, etc. Snakes sometimes gather together in large groups to brumate to help preserve their body heat, and black rat snakes have been found in brumation with copperheads.

We had a black rat snake post-brumation experience a few years ago. To keep the birds from stripping all the berries from our blueberry bushes, I put nets over the bushes one winter. When I checked the bushes in early spring, there were three large black rat snakes trapped in the netting. Clearly they had been there for a while, and they had thrashed around so much that they were completely wrapped in the nets. We spent a couple of hours painstakingly cutting them free from the nets with manicure scissors, starting with their tails of course. They were surprisingly cooperative, but maybe they were in shock? We were kind of in shock, too, and I didn’t even take any photographs. The nets are gone now; both the birds and black rat snakes are happy; and I buy organic blueberries in season from the markets.

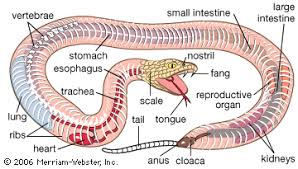

Snakes are reptiles and also vertebrates, as are humans and other mammals… and fish, amphibians, and other reptiles which include lizards, turtles, crocodilians and birds. All these vertebrates have bony skeletons with a spinal cord surrounded by cartilage or bone. Reptiles, which include birds, have unique characteristics among vertebrates. Birds are considered reptiles because they are more closely related to reptiles, especially crocodiles, than to anything else, although birds really are more dinosaurs than anything else. According to the phylogenetic system of evolutionary classification, birds, reptiles, and mammals all share a ancient reptilian ancestor from about 320 million years ago. And fish are also classified as vertebrates because they have a bony skeleton with a spinal cord.

Snakes and lizards are close cousins and together with amphisbaenians (worm lizards) they populate the largest order of reptiles, Squamata, representing approximately 95% of the world’s reptiles with an estimated 92 families and 10,000 species (as of August 2019). There are an estimated 3,600+ species of snakes and 5,000+ species of lizards. There are only two know venomous species of lizards, but 500 species of venomous snakes have been identified with only a small proportion having venom that is harmful to humans. Squamates populate every continent but Antarctica, and they range in size from 25 foot snakes to chameleons smaller then a pencil eraser.

Couldn’t resist putting this photo in from livescience.com. Should we have a naming contest for this tiny chameleon? I vote for “PeeWee”.

Recent research indicates that lizards developed first about 270 million years ago and then, after an exciting period of evolution, snakes radiated from ancient lizards about 128.5 million years ago. This was during the early part of the Cretaceous period which began 145.0 million years ago and ended 66 million years ago, coinciding with the fairly rapid appearance of many species of animals and birds on Earth.

Reptiles are vertebrates with scales on at least some place on their bodies that lay eggs. All reptiles, are ectotherms, cold-blooded animals that cannot control their own body temperature and are therefore dependent on external sources to regulate their temperature, like basking in the sun to warm up. Neither lizards and snakes have a sense of smell comparable to that of mammals. Instead, they have a Jacobson’s organ on the roofs of their mouths, a patch of sensory cells that detects heavy moisture-laden odorous particles. One critical way they both detect their prey is that their flicking tongues pick up chemicals in the air that are then identified by their Jacobson’s organ.

There are, however, two characteristics that easily distinguish the two species: lizards have movable eyelids and external ear openings, like mammals, and snakes have neither. There are some exceptions but generally if it blinks, it’s a lizard. Lizards have excellent eyesight and good color vision, but most snakes have poor vision; they can’t see in color and are able only to detect motion. If you stood stock still in front of a snake, it would not be able to identify you as anything different from a rock or a tree. Instead of eyelids, snakes have a “spectacle” or membrane eye cover over each eye. Both reptiles shed their skins, but snakes shed their skin in one piece with their eye covers, and lizards usually shed their skin in pieces and away from their eyes. Also, snakes are carnivores but lizards are omnivores.

Lizards crush and roughly chew their food, but snakes swallow their prey whole and they have flexible jaws, connected by ligaments and flexible muscles rather than bones, which allow them to eat animals that are up to 10 times bigger than their heads. They drench their live meal in saliva and slowly pull it into its esophagus. From there, the snake uses its sinewy muscles to simultaneously crush its meal and push it deeper into its digestive tract where it is somewhat slowly digested, i.e., broken down for nutrients.

Snakes apparently made some evolutionary trade-offs when they radiated from lizards and their primary senses became taste and small rather than eyesight and hearing.. They gave up ear canals and eardrums as well as their ear openings, so they are mostly deaf, and they developed adaptive heads with highly movable jaws. Eventually, snakes also gave up their legs for a long sinuous and bony body form. Snakes are very bony reptiles, and they are incredibly flexible and fast moving. Adult humans have 24 ribs with 206 bones attached, but snakes have as many as 33 ribs with 1200 bones. They both have all the equipment required to be a mammal, but it’s put together differently, and most snakes only have one functional, simple lung usually the right one.

Although we vertebrates are all lumped together phylogenetically speaking, snakes do have several characteristics that are different from other vertebrates, and this may be why many people fear and almost hate snakes. For example, snakes slither rather quickly and obviously, and they have a cold unblinking stare and a strangely forked tongue that they flicker repeatedly. Also, many people often have an understandable fear that every snake they encounter may be poisonous. An interesting note regarding human fear of snakes is that as many as 15 million people in the U.S. have snakes for pets, mostly pythons. Pythons, which like boas have two lungs instead of the one that most other snakes have, can be quite manageable and interesting pets, living in captivity for up to 25/30 + years.

Snakes in the wild are rather shy and secretive animals and certainly not aggressive, and they never go looking for enemies or bite out of any malicious intent. They are also mostly solitary animals, although they will come together during mating season which is now in Western North Carolina. Snakes are not territorial, although they do have a home range that expands and/or varies depending upon the season and that can overlap with other snakes and animals.

Not many snakes are venomous, and the venom of those that are is designed for defense and stunning prey, not for attacking humans. Venomous snakes have specialized teeth (fangs), and their venom is a highly modified saliva that immobilizes prey and helps break down their tissues for digestion. Although snakes may bite in self defense, how aggressive they seem depends more on the species of snake and how they move rather than if they are venomous or not. If you surprise a snake, or vice versa, stand very still for a short while and then back away slowly. Remember, they cannot see very well and can only detect motion, so standing still when you are startled by a snake is a very good idea. Snake bites are fairly rare in the United States with only one to two thousand reported cases every year with very few fatalities.

Alone among venomous snakes, rattlesnakes can make a distinctive rattling sound when disturbed or frightened. Their rattle at the end of their tail is formed by hollow interlocked segments made of keratin, the same material that composes our fingernails, and they add new segments as they grow. These segments fit loosely together at the end of the snake’s tail, and when the snake is startled, he sticks up his tail and vibrates the muscles around it. It is quite a distinctive and effective sound, especially combined with a characteristic snake hiss! Because they have a sophisticated warning signal, rattlesnakes are considered the newest and most evolved snakes by many evolutionary biologists, and they are found only in North and South American continents.

Of the 3600+ species of snakes in the world, an estimated 106 species are in the United States including 21 venomous species. In North Carolina, there are 38 species of snakes of which 6 are venomous and here in Western North Carolina, 16 snake species have been identified including 2 venomous species: timber rattlesnakes and copperheads.

The copperheads we see are northern copperheads that have the largest range of the five copperhead subspecies. They are found in north as far as Massachusetts, west to Illinois and south to northern Georgia and Alabama. They eat mostly mice but also small birds, lizards, small snakes, amphibians and insects (especially cicadas), The copperhead is the most common and widespread venomous snake in North Carolina and in most areas in the state, it is the only venomous snake. It is estimated that copperheads account for over 90 percent of venomous snakebites, but its venom is the least toxic among the venomous snakes in the state, so its bite is seldom fatal although it is painful.

Timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) are much less common and are listed on North Carolina’s wildlife law as “threatened” because of loss of territory and declining numbers. Both timber rattlesnakes and copperheads are pit vipers named for their specialized pit organs, conspicuous heat sensors located just below and in front of their eyes, that help them locate their prey by their thermal radiation signature.

Flicker.com

pit organ located below and to the front of eye of timber rattlesnake — as with all snakes, no eyelid Generally, timber rattlesnake venom is stronger than that of copperheads and more likely to cause death, but copperheads more often bite people. Timber rattlers are thick-bodied snakes that can grow to be 5-6 feet long and at least 4 inches in diameter. Their average life expectancy is 20 years and sometimes they live much longer. The timber rattlesnakes in the mountains are often colorful snakes with wavy bands and blotches of yellow and black. Timber rattlers are more often rather drab brown or grey colored in other locations but regardless of their body color, the last foot or so of their length is black except for their rattle. Their typical diet is small to moderate-size rodents including squirrels, mice, shrews and chipmunks; small to moderate- size birds; and sometimes other snakes and amphibians. As with copperheads, you have to just about step on rattlesnakes to provoke one to bite, because neither snake is aggressive.

Our rattlesnakes at Richland Ridge are all part of a study so we know where they are…which is close by! And we have never had any incidents.

Project Noah

Another misunderstood and sometimes feared snake in our area is the common northern water snake (Nerodia sipedon), a large, nonvenomous snake native to North America that is never a threat to humans. It is one of the most common snakes in the eastern United States ranging from Maine to Georgia and from the Great Plains to the East Coast. There are several other names for this species, e.g., banded water snake, black water adder, black water snake, spotted water snake, streaked snake, water pilot, and simply water snake. Their diet is mainly fish and amphibians, and they are active both during the day and at night.

Northern water snakes are rather large and heavy-bodied, growing up to 4-5 feet in length, and are usually never more than two or three hundred yards away from a water source. They vary in color and may be grayish, reddish, brown, or black. The front section of their bodies usually has fairly distinct cross bands, but on the middle and posterior portions of the body, the cross-bands become less distinct and can look more like alternating rows of blotches. Northern water snakes usually darken with age so some older snakes may be uniformly dark which makes them easier to identify.

Virginia Herpetological Society

Again, the northern water snake is nonvenomous and harmless to humans, but they are often killed because they superficially resemble the venomous copperhead. Side by side the two snakes can be easily distinguished. The northern water snake has a banded body and will often be a uniformly darker color, but a copperhead has a quite distinctive wavy hourglass-shaped pattern on its body. Copperheads can swim, however, and are sometimes found near the water, so it is wise to remember the copperhead’s distinctive wavy body pattern.

Photo credit: Nature Watch

We have a second species of water snake in Western North Carolina, the queen snake, that is not likely to be confused with a copperhead. They are mid-sized snakes, no longer than 2 feet, generally gray in color but sometimes ranging from light brown to olive green in coloration. They may have three faint darker stripes running down their side, and they have pale yellow bellies with four brown stripes. Queen snake females are quite a bit larger than than males.

Queen snakes have keeled scales and although they are definitely water snakes, they are not as secretive as other snakes and found in varied locations. For example, they are often found with northern water snakes, basking on rocks, and hanging in trees. I have seen them in the beaver ponds atRichland Ridge.

More than half of the snake species in North Carolina are found in our mountainous area with 16 snakes identified in Western North Carolina, including our 2 venomous snakes, compared to 38 species and 6 venomous species found statewide in North Carolina. In addition to the five snakes already described, there are two more snake species seen occasionally in our area of WNC: the eastern garter snake and the small and rather secretive ring-necked snake.

An additional species we have nearby is the worm snake (Carphophis amoenus). They are small, shiny snakes with black, gray or brown backs and pink or whitish bellies. They are common throughout North Carolina, but less likely to be found in the mountains. The worm snake is a burrower so it is seldom seen. It never bites, so if you find one, you can easily hold it and it is a fun, wiggly handful.

And there is one snake in our area I hope to meet sometime, the rough green snake that eats insects and is beautiful and gentle. It is also a popular pet snake.

The additional 7 snakes found in Western North Carolina include:

corn snake more active at night and often found near farms and in barns brown snake common in forested areas and vacant lots

eastern hognose an attractive snake found in woodlands with sandy soil eastern king snake a large secretive snake and one that kills its prey by constriction and has been known to eat copperheads

red-bellied snake a small woodland snake.

smooth earth snake a small harmless snake, it primarily eats earthworms eastern milk snake a larger snake that kills prey, mostly mice, by constriction, usually found in wooded slopes and grassy fields in mountains

We are fortunate to have a snake expert nearby: Steve O’Neil, a naturalist and environmental educator. Steve is the director of the Science Environmental Education Program at Carolina Trails, and a consultant for several organizations. He is conducting the rattlesnake study at Richland Ridge and Earthshine Lodge, and he contributed significantly to this newsletter…thank you, Steve!

You Tube Video Links:

Timber Rattlesnake Tracks

Rat snake Tracks:

Learn more on the Earthshine Nature Website:

www.earthshinenature.com

Follow our adventures on the Earthshine Nature blog:

42 comments