Winter Reading Recommendations

by Linda Martinson

“Everything is connected, absolutely everything.”

Sm’hayetsk Teresa Ryan, forest ecologist, The Mother Tree Project

I read dozens of books last year running the gamut from Ben Okri’s poetry (oh my!) to Code Girls, a surprising book about the brilliant, dogged women who accomplished most of the critical code breaking efforts that helped the U.S. win World War II, to several excellent environmental/naturalist books, many recently published.

So here are some recommendations for Pandemic winter reading. Start with Code Girls. It’s a quick and compelling read and a good lesson that freedom isn’t a given and that the significant efforts that helped us win World War II were not straightforward or obvious! When you finish the book, ponder whether World War II could have been won without the Code Girls?

Next, I recommend diving in and out of Wild, a book of poetry by Ben Okri which is also about freedom. One review of the book noted that, “Freedom is the most precious commodity in the world…” and that in his book, Okri “explores the freedom of our spirit, the child within.”

“So long as you start with your chaos. Order from the chaos you find. The chaos of now, today; of which the order and standards and classics of the past are a part. The way a ruin is part of a forest.”

Here are two books with similar titles, both published in May 2020: In Praise of Walking: A New Scientific Exploration by Shane O’Mara, a professor of experimental brain research at Trinity College in Dublin, and In Praise of Paths: Walking Through Time and Nature. by Torbjorn Ekelund, the founder of the Norwegian nature journal Harvest. Two very different books about the walking and both good reads.

The neuroscientist, O’Mara, describes walking as “the mechanical magic at the core of our humanity” and extols the health benefits and joy that walking gives us. He cites a study published in 2018 that tracked subjects activity levels and personality traits over 20 years. The results indicated that the couch potatoes, i.e., those who moved the least, showed “malign personality changes and scoring lower in the positive traits of openness, extraversion and agreeableness”. His data also indicate that regular walkers have lower rates of stress, depression and anxiety and enhanced learning, memory and cognition.

“One of the great overlooked superpowers we have is that, when we get up and walk, our senses are sharpened. Rhythms that would previously have been quiet, suddenly come to life, and the way our brain interacts with our body changes.”

With In Praise of Paths, Ekelund wrote an experiential book about walking and how it changes us that is linked to the myths and lore of paths. After he was diagnosed with epilepsy as an adult and lost his driver’s license, Ekelund began walking everywhere, even walking four miles to buy groceries and then back again with his groceries in a big backpack. As he began to walk everywhere, he became enthralled with the spontaneity of the paths that develop wherever people walk to and fro. “The world’s largest religions,” he writes, “all make use of path metaphors. … The metaphorical implications of the path are obvious and easy to understand because, in a way, life is all about choosing the right way.” He describes walking as a spiritual exercise or vision quest in which “a key strategy for finding ourselves is to first get lost.”

You will find yourself wondering about familiar paths after reading this book; for example, how/when did they develop, why do they meander off in this direction and not that way, and who is walking on them?

Here is another compelling book published in 2020 and also written by a Scandinavian author: The Book of Eels. The Swedish author, Patrik Svensson, describes his book as “very strange and nerdy”. The biology of eels has been investigated by some very influential scholars including Aristotle and Freud. It took Johanne Schmidt, a Danish marine biologist, 20 years to discover that all European and American eels go to spawn in the Sargasso Sea, a relatively small section of the Atlantic Ocean that begins about 300 miles off the eastern coast of the U.S. Svensson alternates some evocative boyhood memories of nighttime fishing trips for eels with equally evocative descriptions of the natural history of eels. The Book of Eels is a best seller in Svensson’s native Sweden where it won the August Prize, the country’s most prestigious literary award.

Helen Macdonald has been described as writing with “heart-tugging clarity”, and she has just published her fourth book, Vesper Flights. It is a collection of her best essays and some new pieces on wide ranging topics, for example on the concepts of captivity and freedom; nostalgia for a vanishing countryside; and how we make sense of the world around us.

Her last book, H is for Hawk, is also an excellent read. Macdonald has written, “It is hard to write about the natural world without writing about grief.” This sad statement is a good introduction for the next recommended book: Losing Earth: A Recent History by Nathaniel Rich.

Apparently, by 1979 all the compelling data about climate change had been published, including how to stop it. And during the next decade, to 1989, a desperate campaign was mounted by a few brave scientists, politicians, and environmental strategists to convince the citizens of our planet to act before it was too late, and it almost worked…but it didn’t. In August 2018, an entire issue of the New York Times Magazine was devoted to the story, “Losing Earth; The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change” by Nathaniel Rich. This influential article was expanded into a book, Losing Earth: A Recent History, by the same author and published in 2019. The book includes previously unreported data about climate change; climate denialism; and the coordinated effect of the fossil fuel industries to thwart climate policy development.

Losing Earth: A Recent History was described in a book review giving it a 5.0 star rating as, “…the rarest of achievements: a riveting work of dramatic history that articulates a moral framework for understanding how we got here, and how we must go forward.”

Other recent exciting scientific writing have been about

1. the tangled transfer of horizontal, not just vertical, transfer of DNA, i.e.,horizontal gene transfer. And hidden in the soil,

2. the Wood Wide Web, an underground network of microbes that connects trees.

David Quammen’s book about horizontal gene transfer, The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life, published in 2018, was a New York Times best seller and he was described as “our greatest living chronicler of the natural world”….and his book, as revealing the “scientific struggle to understand horizontal gene transfer.”

Here is an example of horizontal gene transfer:

Chimpanzees and bonobos are the closest living biological relatives to humans, but we did not evolve directly from any primates living today. Our species and chimpanzees, for example, diverged from a common ancestor primate species that lived between 8 to 6 million years ago. We also share 97% of our DNA sequence with orangutans but of the great apes, orangutans are the most distantly related to humans, while chimpanzees are the most closely related. Why? Because somewhere along the way, as humans experienced large-scale structural rearrangements in our DNA that probably accelerated our evolution, a chunk of orangutan DNA got incorporated into human DNA, probably by a virus that first infected orangutans and then humans. Voila! Horizontal gene transfer!

Quammen is an excellent and accessible writer; he has written 15 books, published 200+ articles, and received several literary awards. Right now he is in the news because of his 2012 book, Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic, that vividly and accurately presaged our present Pandemic.

Quammen’s comments about the recent Pandemic: “We are all connected, and this Pandemic reminds us of that in a gruesomely vivid way. Bats, monkeys, apes, pangolins, civets, people; we are all animals, living together on a single small planet, dependent not just upon one another but also on the ecosystems we inhabit…. Zoonotic spillovers will keep coming, as long as we drag wild animals to us and split them open…..A tropical forest, with its vast diversity of visible creatures and microbes, is like a beautiful old barn: knock it over with a bulldozer and viruses will rise in the air like dust.”

“Why David Quammen is Not Surprised” orionmagazine.org March 17, 2020

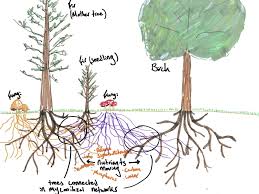

The Wood Wide Web is down there, hidden in the soil everywhere trees grow. Dr. Suzanne Simard is a forest ecologist at the University of British Columbia who has been studying the forests of Canada for over thirty years. She coined the term, Wood Wide Web, when she published an article in Nature, August 7, 1997: “Net Transfer of Carbon Between Tree Species in the Field.” She discovered through her research that there are complex, symbiotic networks in forests, especially old growth forests, that mimic our own neural and social networks. What Dr. Simard found most intriguing is that not only can the roots of the same species of trees connect and share resources, different species of trees can also communicate at some level and share resources, too.

After her seminal article, other scientists gradually began to validate Simard’s concept of a Wood Wide Web. For example, German forester, Peter Wohlleben, wrote a New York Times bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate, translated from German into English in 2016, in which he stated, “most individual trees of the same species growing in the same stand are connected to each other through their root systems…and can share sugars, water, minerals, and chemical signals.”

A sketch of

Wood Wide Web communication

by Suzanne Simard

npr.org

A long article was published in the August 7, 2016 issue of the The New Yorker: “The Secrets of the Wood Wide Web” by Robert Macfarlane, and the headline was: “In London’s Epping Forest, a scientist named Merlin eavesdrops on trees’ underground conversations.” And there was definitely some foreshadowing of Sheldrake’s yet-to-be written seminal book in the article. Macfarlane described the relationship between these mycorrhizal fungi and the plants they connect as largely one of mutualism in which both organisms benefit. He added that this symbiosis is now known to be ancient, around four hundred and fifty million years old, and that “recent scientific revelations raise big questions about what trading, sharing, or friendship might mean among plants.”

A search for the Wood Wide Web in the World Wide Web turned up an excellent article, “The Wood Wide Web” by Emily Stone in her bookstore’s newsletter: Northern Wilds Magazine, October 30, 2017. She wrote, “If you follow the roots of almost any plant out to their very tips, you’ll find fungal mycelia. Some fungi just sheath the roots; others actually tap into the root cells. Each plant has its preferred method of connection, and certain species of fungi that it consents to form relationships with. Fungal mycelia extend the plants’ reach into the surrounding soil. This mycorrhizal (myco=fungus; riza=root) network is robust and thickly woven. So thickly, in fact, that scientists say you could “find seven miles of fungal hyphae in a pinch of dirt, and hundreds of miles under a single footstep.”

A fiction book based on Suzanne Simard’s research, The Overstory, by Richard Powers won a 2019 Pulitzer Prize, and Ferris Jabr wrote a long article “The Social Life of Forests” for The New York Times on December 2, 2020. Jabr wrote his long and compelling article with significant input from Simard about her mission to convince loggers to retain some vigorous and mature “mother trees” instead of clear cutting all the trees. He recounts a description of part of The Mother Tree Project, the 230,000-acre Menominee Forest in northeastern Wisconsin, that has been sustainably harvested for more than 150 years.

The forest is on the Menominee Indian Tribe reservation, and it has never been clear cut. Instead the forest managers harvest low-quality and ailing trees for lumber and keep the most vigorous trees, allowing them to grow up to 200+ years old. These are the “mother trees” that Simard advocates having in any forest. Since 1854, the tribe has sustainably harvested more than 2.3 billion board feet, almost twice the volume of the entire forest, yet there is now more standing timber than when the logging began. The tribal spokesman explains, “To many, our forest may seem pristine and untouched but in reality, it is one of the most intensively managed tracts of forest in the Great Lake States.”

The climax of all this writing about the Wood Wide Web will be Suzanne Simard’s book (her first one!), Finding the Mother Tree, expected to be published in May 2021.

Simard describing connections between tree roots and fungal network

“Web of the Woods.” Allura Petersen. The Planet Magazine

3/16/2017

More poetry from Ben Okri’s book Wild

“You love the moon

And are kind to strangers

And your serenity

Dissolves all dangers

I need someone to sing

To can I sing to you”

References:

“NIH-funded scientists publish orangutan genome sequence.” nih.gov. January 26, 2011.

Note: The chimpanzee, orangutan and human genome sequences, along with those of a wide range of other organisms, can be accessed through the public genome browser: GenBank at NIH’s National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCB)

theguardian.com July 2019. “It’s a superpower—how walking makes us happier, healthier, and brainier.” In Praise of Walking: A New Scientific Exploration by Shane O’Mara.

Washington Post book review “The Tangled Tree, A Challenge to Darwin’s Branching View of Evolution.” Jerry A. Coyne August 23, 2018

Book review in the journal Science on August 7, 2018, by Igor T. Knight “An Engaging History Reveals the Scientific Struggle to Understand Horizontal Gene Transfer.”

44 comments