Celebrating Moths and Learning More About Lichens

by Linda Martinson

National Moth Week is July 17-25 this year, and it is the tenth year of celebrating moths with a worldwide citizen science project. National Moth Week was founded in the United States in 2012 by the Friends of the East Brunswick Environmental Commission, a non-profit organization in New Jersey. In all 50 U.S. states and in 80+ countries worldwide, scientists and other enthusiasts survey moths during the week, mostly at night, to study and record their populations. And National Moth Week is also a celebration of the amazing biodiversity of moths and their ecological importance.

Lepidoptera is a large order of insects that contains moths and butterflies; the fourth-largest insect group worldwide containing 10 percent of the total described species of living organisms. There are possibly as many as 500,000 species of moths and butterflies extant—with almost 200,000 identified in 126 families and 46 superfamilies and thousands not yet found nor identified. In the United States and Canada alone, more than 750 species of butterflies and 11,000 species of moths have been recorded. Indeed, some entomologists lament that the numbers of moths and butterflies are declining faster than the number of species can be identified.

The organizers of National Moth Week have partnerships with major online biological data depositories, and participants map and photograph moth distributions all over the world to gather data to estimate their numbers; their distribution; their health; and their life history, for example. They also encourage collecting voucher specimens, i.e., parts of or wholly preserved moths, to obtain DNA samples. Observations and data collected during National Moth Week are filling in some important information gaps; as stated on their website: “The contributions of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists form the foundation of many aspects of our understanding of moth ecology.”

How do butterfly and moth species differ? Lepidoptera are primarily different from other insect species because both moths and butterflies have external scales, especially on their wings Also, both species lay eggs and start life as caterpillars. Finally, both species are ancient; there are some estimates that moths and butterflies evolved from a common ancestor about 250 million years ago. Generally, they have been split into three broad groups: micro-moths, macro-moths and butterflies.

There are no simple “rules” for distinguishing moths from butterflies although some general distinctions are often touted. For example, moths are fuzzy and butterflies are smooth; butterflies are more colorful than moths; the wing structures of the different species are distinct; and moths are generally more active at night than butterflies and especially tuned into bats, their main predators. However, none of these distinctions hold completely true and in general, moths and butterflies share the same basic biology and have more similarities than differences. And according to a description from the U.K Natural History Museum (nom.ac.uk): “Butterflies are (in the evolutionary scheme of things) just big, flamboyant, day-flying (medium-sized) moths.”

Note: In July 2015, Dr. David Horn, a well-known entomologist, visited us and collected and identified 79 species of moths. Perhaps my contribution to National Moth Week could be to convince Dr. Horn to conduct a follow-up comparison study. That comparison might be depressing, however. Sadly, the populations of moths and butterflies, as with other insects, are declining although, within the Lepidoptera order, not everywhere and not within every species.

Cecropia moths are beautiful silk moths with a wingspan of five to seven inches. It is the largest moth found in North America.

Prochoreutis inflatella, a micro-moth with a wingspan of 9-11 mm

Micro-moths range in wingspan from 1.2 (tiny) to 15 mm (medium-sized). The smallest may be the tiny “flies” you sometimes see flitting around your kitchen in the late night/early morning

BugGuide.net image

And on to lichens…

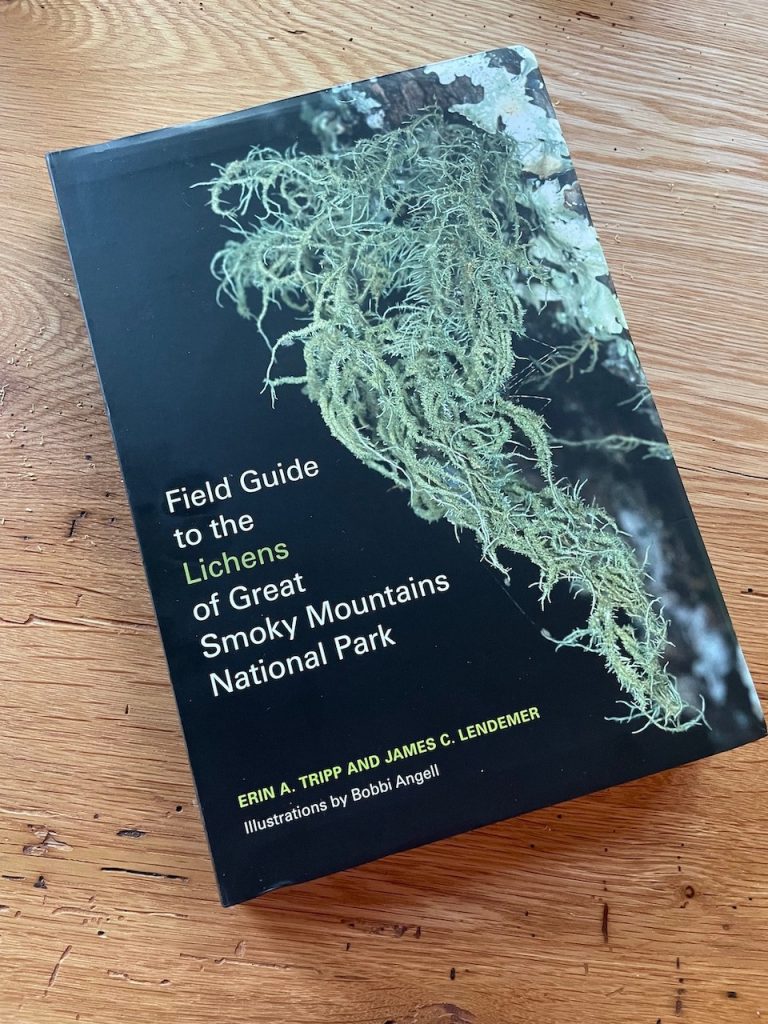

Here is an elegant, but also easy-to-read and informative book, described as “lovingly prepared,” for both your summer reading and for a summer project of identifying some of the lichens around you: Field Guide to the Lichens of Great Smoky Mountains National Park by Erin Tripp and James Lendermer with illustrations by Bobbi Angell, published in 2020. They reported more than 920 lichen species occurring in the GSMNP, and they illustrate more than 600 species with photos, notes and key features in their book, an awesome task. The authors logged +2000 miles on foot on and off the trail and each photograph in the book is tied to a physical voucher specimen that they have housed in the NY Botanical Garden Herbarium, the University of Colorado Herbarium or both. The authors emphasize, however, that no field guide is ever complete, and they predict that numerous lichen species have yet to be discovered in GSMNP.

I wrote a short newsletter about lichens in 2015, so much of the first three sections in the book was familiar to me from my research then. Lichens are neither plant nor animal; they form rather than grow, and they are a unique mutualistic symbiosis among organisms from three different kingdoms: fungi, algae, and cyanobacterium. When two or three organisms give up their individual identities and change forever into lichens, they can go together as one where none of the organisms could go alone. For example, algae alone can only live where it is moist and fungi alone can only grow where there is decomposing matter to support them, usually underground. A lichen composite, however, can live almost anywhere although they are scarce in highly polluted areas and in mono-culture forests, i.e., with a limited variety of trees all of about the same age.

There are at least 20,000 species of lichens found on every continent on Earth; in virtually every ecosystem; in all climates; and at every altitude. Lichens can live, even flourish, in extremely harsh environments although they are sensitive to air pollution. After any natural disaster from fallen trees from a hurricane to the end of the Cretaceous Period 65 million years ago, when almost all life was destroyed, lichens begin to rebuild life, often on barren and even completely toxic surfaces. Lichens also directly benefit humans through their ability to absorb pollutants in their atmosphere.

Ed Yong, a captivating scientific writer, refers to lichens as “gorgeous and weird…(having) pushed the boundaries of nature and how we study it.” Lichens do not have roots, stems or leaves; they are organisms created by symbiosis and there has been a scientific realization that lichens take symbiosis to an extreme. Erin Tripp, the first author of the Field Guide, is one of the main players in recent lichen symbiosis research, and this continuing research on lichens is described and well written in the Field Guide. And certainly it is critical and exciting work because the 814 square miles of Great Smokies National Park contain 1/5 of lichen species in North America.

The authors of the Field Guide don’t go deep into lichen chemistry (they leave that for their other more technical book about lichens), rather they log 600+ lichens that they have found, photographed, and described in the book alphabetically by genus and species. With each lichen photo, there are notes about its habitat and ecology; a range map; a brief chemistry description; and key features. Even with appealing, easy-reading descriptions, just leafing through the descriptions and illustrations of the 600+ lichens the writers describe is daunting, and this statement in the book rings true: “Lichens are highly complex structures with seemingly endless evolutionary modifications to morphology.” I think that means it’s difficult to identify lichens; to remember their scientific names; and to distinctly describe their characteristics and differences…plus they are highly complex.

That said, the authors gave it a great try in this book to make the hundreds of descriptions readable and distinct, even giving all the lichen species common names, such as “Fish on Chips”, “Unraveling Twine”, and “Yellow-All-Over Lichen”. (Note: Many of these names seem a bit contrived…possibly created over a bottle of wine at the end of a long day of collecting and cataloging lichens?) Given the challenge of distinguishing and describing 600+ lichen species, the research, writing, information about lichen biology, illustrations, photos, and classifications are impressive and valuable. And the illustrations for the section of the book on lichen biology are exquisite. The authors certainly made a gallant try to write for “both researchers as well as casual observers”. Also, the Field Guide is handsome and looks great on our coffee table.

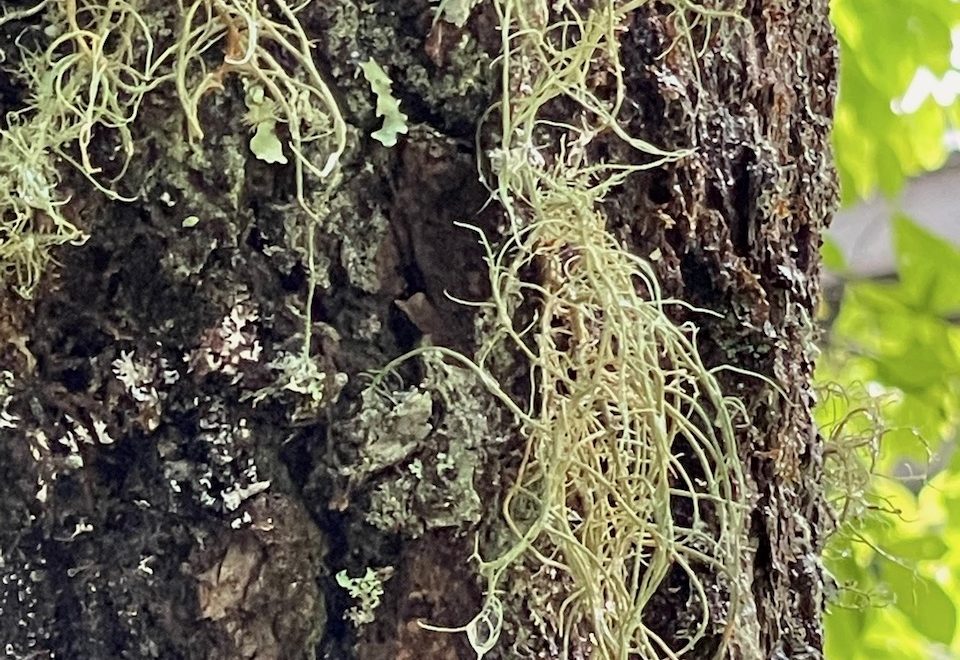

So, inspired by this awesome book about lichen biology with its hundreds of descriptions and photographs, I decided to photograph some of the lichens on trees around our house (it’s been a rainy summer and there are plenty of them) and to identify them using the field guide section in the book. The “body” or vegetative tissue of a lichen is called a “thallus” and lichens are often described by their thallus and where it fits within common groupings of lichen thallus growth forms such as fruticose, “growing like a tuft or multiple-branched leafless mini-shrub, upright or hanging down, 3-dimensional branches with nearly round cross section or flattened” or crustose, “crust-like, adhering tightly to a surface like a thick coat of paint”. So I decided to first try to identify the thallus in each of my lichen photos. Then I would try to find a corresponding lichen thallus image among the 600+ photos in the book, making sure the range map corresponded with our location.

And….well….it didn’t take long for me to realize that it could take me the rest of the month, possibly longer, to accurately figure out what lichens species I had photographed using the comparisons of the photographs in the book, even if I narrowed them down by lichen thallus growth forms. And so, I punted. Below are some of my photos of lichens near our house. I will continue to attempt to identify them, and perhaps someone will volunteer to help me? Meanwhile, the Field Guide is a wonderful book, and I look forward to using it to identify the many amazing lichens, perhaps hundreds of them, at Richland Ridge.

Additional references:

Lees, David C. and Zilli, Alberto 2019, reprinted with updates 2020. Moths: a complete guide to biology and behavior. Smithsonian Books Washington, DC

Moskowitz, David and Haramaty, Liti, July 26, 2016. Got Moths? Celebrate National Moth Week and Global Citizen Science. Entomology Today

Lichen. Wikipedia last edited on 25 June 2021

Moth. Wikipedia last edited on 18 June 2021

McNamara, Alexander, November 2019. Lichen age discovery reshapes understanding of complex ecosystem evolution. BBC Science Focus Magazine

U.S. Forest Service About Lichens. www.fs.fed.us

Yong, Ed, July 21, 2016. How a guy from a Montana trailer park overturned 150 years of biology. The Atlantic

Yong, Ed, January 17, 2019. How lichens explain (and re-explain) the world. The Atlantic

27 comments