Celebrating Convergences and Whippoorwills

by Linda Martinson

Convergences are notable. Some are simple; for example, waking up at 5:55 am and then sitting down to eat at 5:55 pm or that three people you know share the same birthday on April 13. There was, however, a very special convergence this year: a rare overlap of major religious observances in one week. On Friday, April 15, Jewish people celebrated Passover marking the exodus of Israelites from enslavement in Egypt; on the same day, Christians observed Good Friday to commemorate the crucifixion of Jesus before Easter Sunday; and over the weekend of April 15, Muslims continued the observation of Ramadan, a month of prayers and fasting memorializing the transmission of the Koran. And as I was working on this newsletter, we celebrated Earth Day!

This overlap of these three religious observances occurs only about every 33 years, another strange convergence because 33 is an interesting number. It has been called “A Master Number” throughout many different divinities, organizations and practices. For example, 33 is three times the number eleven which makes it an odd number with the factors of 3 and 11, two other odd numbers. The number 33 also appears as a notable number with several religious implications. For example, the number of deities in the Vedic Religion is 33 and 33 is the numerical equivalent of AMEN: 1+13+5+14=33. And in science, there are 33 vertebrae in a normal human spine.

Easter weekend this year was special for me because on Saturday night, April 16, my daughter woke me up in the middle of the night to come listen with her to the whippoorwills (also spelled “whip-poor-wills”) calling. Because I am usually early- to-bed, I rarely hear night birds calling or any other night noises for that matter. So this was an especially different and exciting night for me! The moon was full and at its peak size, and we could clearly see everything outside. It was a calm and lovely night, and the whippoorwills were indeed calling. There is something about the middle of April that is special…everything in Nature is waking up and popping up, and now I know that some critters are staying up all night to celebrate.

Whippoorwills are in the same scientific family as nightjars that range in California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and west Texas, and nighthawks that range mostly in Mexico and Central America. For years, all whippoorwills were considered one species. In 2011, however, whippoorwills were split into two species mainly based on distinct differences in their DNA sequencing; range; egg coloration, and vocalization. The Eastern population is now referred to as Eastern whippoorwills with the scientific name Caprimulgus vociferus, and the population located in the southwestern United States and Mexico is now referenced as the Mexican whippoorwill, Antrostomus arizonae. Eastern whippoorwills are found across central and southeastern Canada and the eastern United States. They typically breed and live in rich moist woodland areas, often in second growth forests as in Richland Ridge. They seem to avoid large areas of uninterrupted forest with dense canopy.

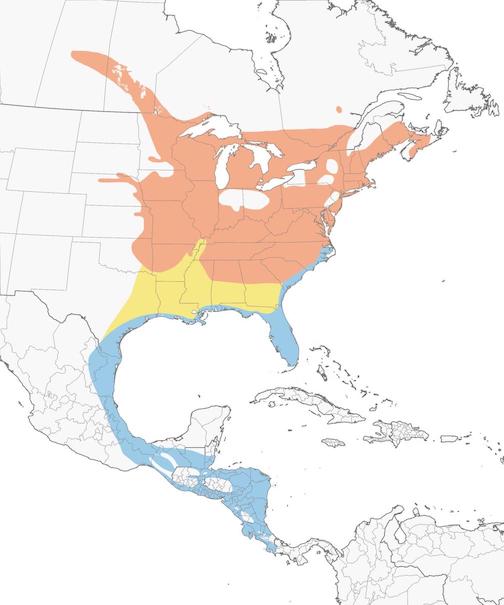

Migration- yellow; Non-breeding- blue; Breeding- orange

Eastern whippoorwills are medium-distance migratory birds. They migrate to eastern Mexico and Central America for the winter, apparently flying mostly over land. In the spring, they migrate back to their breeding grounds between late March and mid-May. Not much is known about how they navigate and time their southward migration routes, but they do sometimes form loose flocks when they migrate south usually between early September and late November.

The whippoorwill is about 8 to 10 inches long, bigger than a robin and smaller than a crow. They have a wing span of 17 – 19 inches. Whippoorwills have rather short legs; a long rounded head with large eyes; a stout chest; and a long tail and wings. Their bills are relatively small, but they can open their mouths very wide… the better to scoop up insects when they are swooping around at night.

Whippoorwills have mottled plumage: gray, black and brown on top and lighter gray and black on the bottom and with a dark throat. The corners of the male’s tail are white and males also has a thin band of white feathers around their necks. Females are usually lighter colored but still have mottled plumage. Whippoorwills are well camouflaged by their mottled feathers, and not often seen day or night.

Whippoorwills forage at night catching flying insects and usually sleep during the day. They are often heard at night, but they are less commonly seen then. The best time for seeing them is around dawn and dusk or on moonlit nights when they are swooping across the sky searching for food, but they can be heard all night. It is perfect that they are named for their song, because they can repeat “whip-poor- will” as many as 400 times without stopping. Whippoorwills seem to locate insects by seeing the silhouettes of the bugs against the sky. Their eyes have a reflective structure behind the retina that is probably an adaptation to flying in low light conditions.

Eastern whippoorwill nests are simple: they nest on the ground in a small pile of dead leaves and usually lay only two eggs at a time. They are well camouflaged on their nests with their mottled plumage and will lie there without moving unless they are almost stepped upon. Even if they are not nesting, whippoorwills often roost on shaded gray-brown leaf litter in open forests or stretched out lengthwise along a branch. Eastern whippoorwills usually lay their eggs in phase with the lunar cycle, so their eggs hatch about 10 days before a full moon. With the moon nearly full, the whippoorwills can forage most of the night and scoop up lots of insects for their chicks.

Whippoorwill chicks are active nestlings, probably because moving around makes it more difficult for predators to rob their nests. Whippoorwill parents help by shoving nestlings around with their claws if predators are near, sometimes sending the young birds tumbling far away from the nest. Wild whippoorwills typically live 13 to 15 years.

This nestling is certainly well camouflaged! The nestling period, when their eyes are closed, is only 3-8 days. As soon as their eyes open, the female leaves the care of the nestlings to the male, and often quickly hatches a new clutch of eggs nearby. Male whippoorwills spend some time protecting their territories during nesting season, but they are generally solitary.

Sadly, the Eastern whippoorwill is becoming rare in several areas. In 2017, it was up-listed from “least concern” to “near threatened” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of threatened species. Based on citizen science observations, populations of the Eastern whippoorwill had declined by over 60% between 1970 and 2014. Several reasons have been proposed: e.g., increased forest disturbance; pesticides; and intensified agriculture which have all caused heavy declines in the flying insect populations that the Eastern whippoorwill depends upon.

Several organizations like BirdLife International have started initiatives, for example the Conservation Reserve Program, which have made considerable strides in conserving several species of birds and reversing its decline. The program is a cost-share and rental payment initiative of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). In this program, the U.S. government pays farmers to take certain agricultural croplands out of production and to convert them, for example, to vegetative cover, preferably cultivated or native grasslands; wildlife and pollinator food and shelter. The purpose of the program is to reduce land erosion, improve water quality and increase wildlife habitat. The Eastern whippoorwill is one of the species designated to benefit from this program. Let’s hope the program works— whippoorwills are amazing birds.

And a reminder, don’t miss an exciting celestial event coming soon: a Total Lunar Eclipse on May 15-16, 2022. And it will be super moon eclipse because it will happen just before the moon reaches its closest point to earth for the month which will make it appear relatively large in the sky. And it will also be a blood moon because, during a total eclipse, the earth lines up between the moon and the sun. Because earth will be blocking most of the sunlight from the moon, the remaining light reflecting onto its surface gives the moon a red glow. A blood moon occurs only during a total lunar eclipse.

Luckily, this super moon event in May happens at a (fairly) reasonable hour. The partial eclipse begins at 10:27 pm on Sunday, May 15, and totality (as the moon is engulfed in the Earth’s shadow) begins at 11:29 pm and and reaches totality at 12:53 am on Monday, May 16. The duration of totality is about 85 minutes, and this total eclipse is “central” which means the moon will pass centrally through the axis of Earth’s dark shadow. This will indeed be a super moon event so cross your fingers for clear skies on the night of May 15.

Finally, thank you to my wonderful daughter, Aina, for suggesting that I write a newsletter about whippoorwills. What a great idea!

41 comments