Walking Sticks and More

by Linda Martinson

We had an exciting surprise one fine August morning: a walkingstick on our car door handle. They are not uncommon but they are rarely seen, mainly because they are shy and generally nocturnal and most active between 9 PM and 3 AM. Also, imagine how well camouflaged they are on the ground or on trees. Note: this one is not upside down on the handle — what might look like its head in this photograph is actually its “tail”.

This seems to be a Northern Walkingstick, the most common of six species in North America, with a range from the Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida, west to California and north to North Dakota. It also occurs in Canada where it is the only stick insect.

There are 3,000 species of walkingsticks worldwide of the order Phasmatodea, and they are unique in their physiology, resembling a twig, slow moving and well camouflaged. Walkingsticks used to be classified with grasshoppers, but now they have their own classification: Diapheromera femorata. The males are about 3 inches long and brown; the females are up to 4 inches long and more greenish-brown in color. Ours seems to have been a male as does the one in this photograph.

Northern walkingsticks can’t fly because neither sex of this species has wings, and they move slowly. They are terrestrial and vegetarian and eat (probably also slowly) the deciduous leaves of trees and shrubs. Besides looking like twigs, walkingsticks use behavioral camouflage, too. During the day, they stretch out somewhere (usually with better camouflage than a car door handle) and extend their antennae and front legs to the front and stretch out their rear legs to the back remaining motionless or swaying gently for hours. Like all insects, walking sticks have six legs, and they can sacrifice a leg if a predator grabs it.

Females also lay their eggs slowly, one at a time, dropping them randomly on the ground in the early fall. Their eggs look like seeds, small, oval, and hard-shelled, and they have a shell layer with a capitulum, a knobby bump that tastes good to ants. Hopefully, ants find the eggs before wasps do. Wasps and some other predators devour them immediately if they find them, but ants carry the walkingstick seeds to their nests. There they eat the capitula and toss the inside part of the eggs onto their waste heap which is a well protected place for them. The tiny walkingstick nymphs hatch in the spring, and the ants allow them to safely exit the ant hill. Note: There are other plants and animals that enjoy partnerships with ants, and they are all called myrmecophiles.

The new walkingstick nymphs climb up nearby vegetation and hang on to the bottom of leaves and start eating. Stick insects molt up to four to eight times before they are full sized adults, taking from three months to a year, and they usually eat their leftover skins after they shed them In general, female walking sticks are larger than males because they have bigger abdomens to hold their eggs.

Perhaps because they don’t move around much, Northern walkingsticks sometimes reproduce through parthenogenesis, a process sometimes called “virgin birth” in which unfertilized eggs hatch as carbon copies of the female that produced the eggs. As a result, male walkingsticks are much less common than females. Some do manage the conventional male/female mating and it is generally a slow process, too. During mating, a male and female walkingsticks will remain coupled together for several hours, days or even weeks.

uwm.edu photo

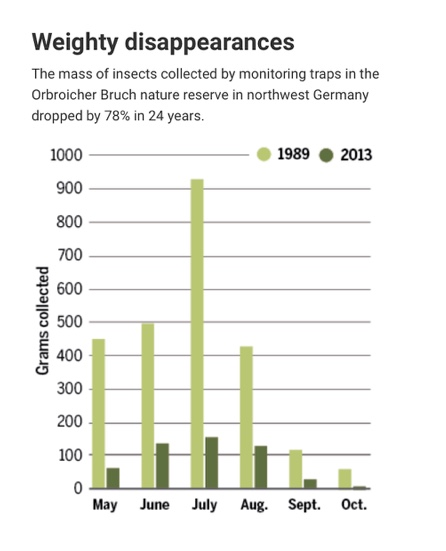

There is so much we don’t know about insects, and we’re running out of time to identify and learn about all the insect species. The scientific estimate is that there are about 5.5 million insect species, and only a fifth of them have been identified and named. A second estimate is that one million animal and plant species on Earth are now facing extinction and half of these are insect species.

There have been five mass extinction events in the history of Earth, each caused by catastrophic environmental events wiping out between 70 to 95% of the species of plants, animals and microorganisms. The most recent was 66 million years ago when a massive comet smashed into Earth causing a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on the planet including dinosaurs. The sixth mass extinction, the one that is happening now, is estimated to eventually wipe out one million animal and plant species, And it is different because it is being caused by humans rather than by a severe environmental event.

In 1992, 1,700 of the world’s leading scientists, including a majority of Nobel laureates in the sciences. published an appeal that begins:

“We the undersigned, senior members of the world’s scientific community, hereby warn all humanity of what lies ahead. A great change in our stewardship of the earth and the life on it is required if vast human misery is to be avoided, and our global home on this planet is not to be irretrievably mutilated.’

In 2017, they issued a second graphic warning that was eventually signed by 20,000 scientists, and now they have issued a new study: “Scientists’ warning to humanity on insect extinctions”, published in the journal Conservation Biology in February 2020. It is a third stark warning to humanity and includes these statements: “Half of the one million animal and plant species on Earth facing extinction are insects, and their disappearance could be catastrophic for humankind….The main drivers are dwindling and degraded habitat, followed by pollutants — especially insecticides — and invasive species”.

The facts and biology behind these grim warnings indicate that, “Human activity is responsible for almost all insect population declines and extinctions”, and the team of scientists behind the basic research developed a simple nine-point plan that we can all follow to contribute to insect survival:

1. Avoid mowing your lawn frequently; let nature grow and feed insects

2. Plant native plants; many insects need only these to survive

3. Avoid pesticides; go organic, at least for your own property

4. Leave old trees, stumps and dead leaves alone; they are home to countless insects

5. Build insect hotels with small horizontal holes that can become their nests

6. Reduce your carbon footprint; this affects insects as much as other organisms

7. Support and volunteer in conservation organizations

8. Do not import or release living animals or plants into the wild that could harm native species

9. Be more aware of tiny creatures; always look on the small side of life.

And E.O. Wilson, an American biologist recognized as the world’s leading authority on ants, also recommends: “Pay attention to the little things that run the world”.

Many large creatures need protection, too, so let’s celebrate World Elephant Day every year on August 12. There is much to admire about elephants. They are intelligent, family-oriented, and have amazing memories. Unfortunately, they also have valuable ivory tusks. The World Wildlife Foundation estimates that about 20,000 African elephants are illegally killed every year for their ivory…more than are born every year. A century ago, there were an estimated 12 million elephants in the wild. Today, the estimate is that there are as few as 400,000 wild elephants remaining.

To celebrate World Elephant Day, the Atlantic magazine this month featured several stunning photographs of elephants in the wild. Here is one of them taken by Greg Du Toit in Botswana’s Mashatu Game Reserve.

We could have started celebrating World Elephant Day on August 12 by watching the Perseids meteor shower in the pre-dawn hours. They were most visible this year on August 12 and 13, but can still be seen from the northern hemisphere until August 24. Normal rates seen from unlighted locations range from 50-75 meteors per hour. The Perseids are the particles released from the comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle during its many returns to the inner solar system. They were named the Perseids because the area of the sky in which they are seen is located near the prominent constellation of Perseus named after the “greatest Greek hero and slayer of monsters before the days of Heracles”. Look up and to the north just before dawn on a clear night or you watch a clip of the meteor shower on space.com Perseid meteor shower 2020. They have a fine explanation of the Perseids and this great image taken by David Kingham of the Perseid meteor shower in the Snowy Range in Wyoming, 2012.

Finally, a book recommendation: Some Assembly Required: Decoding Four Billion Years of Life, from Ancient Fossils to DNA written by Neil Shubin, who has some credibility as a professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago and the provost of the Field Museum of Natural History. He covers a lot of ground in his book from a history of Victorian England and the amazing scientific foresight of Charles Darwin to the latest research and discoveries of powerful transformations in evolution.

A review in inquisitivebiologist.com, describes the book as “a very pleasant mix of the latest science, the historical root of ideas and the people behind them.” It is that, and he includes many descriptions of the contributions of women scientists; for example, the ground-breaking ideas of Lynn Margulis on endosymbiosis that were completely rejected for years and Nicole King’s work on choanoflagellates, the single-celled creatures that have been identified as the closest living relative to multicellular life forms.

Without sacrificing relevant scientific information and data, Shubin gives simple and elegant descriptions of some complicated questions and ideas. For example, the genome sequencing of humans and chimpanzees reveals a 95 to 98% similarity which is remarkable. Why is this when we are so different? He explains that DNA is not just a molecule containing gene after gene after gene. It is more like a circuit board, a network where some pieces of DNA function as switches that turn other genes on and off. And some of these genes “jump” — they are transposable elements, i.e., DNA sequences that move from one location on the genome to another.

Shubin credits geneticist Barbara McClintock with the discovery of jumping genes 50 years ago, when most biologists were skeptical of her research. Now the concepts of DNA functioning as a circuit board with jumping genes are accepted, and it has been discovered that jumping genes are found in large numbers in almost all organisms. For example, jumping genes make up approximately 50% of the human genome and up to 90% of the corn genome.

This book contains several lively descriptions of the field of evolutionary development, or “evo-devo” as Shobin refers to it, a field in which the research demonstrates again and again how evolution can “reuse, repurpose, or re-jiggle already existing structures and processes.” And more than once, Shobin evokes a quote from Lillian Hellman: “Nothing, of course, begins at the time you think it did.” This quote seems apropos when thinking about this pandemic we are immersed in now, doesn’t it?

Other References:

Northern Walkingstick (Family Diapheromeridae)

October 19, 2016. University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Field Station

Scientists’ warning to humanity on insect extinctions. sciencecodex.com April 6, 2020.

University of Helsinki. “Scientists warn humanity about worldwide insect decline: They also suggest ways to recognize and avert its consequences.” ScienceDaily, 10 February 2020.

Wirth, Chris (31 December 2011). “Species Diapheromera femorata: Northern Walkingstick” (http://bugguide.net/node/view/34736). Iowa State University Entomology.

23 comments