Nature Notes April 2018

by Linda Martinson Certified Blue Ridge Naturalist

Living in rural Transylvania County, we rarely see bears although we know they are here; we see the signs of their activity and we catch glimpses of them galloping across a road well ahead of our car or at the edge of the trees just for a moment before they disappear back into the underbrush. Oddly enough, if we wanted clear bear sightings, our best bet would be to spend some time looking for them in and around Asheville. About 8,000 to 10,000 bears range across Western North Carolina, and many of them meander in and out of urban and suburban Asheville, the 11th most populous city in the state with a population of about 90,000 and growing.

The legends of the earliest residents of the area e.g., the mound builders 5,000 years ago, as well as the documents of the early explorers from the Old World describe black bears as teeming through the mountains, the Piedmont and all along the coast of what is now North Carolina. In 1774, naturalist William Bartram complained about them in his journal, writing, “the bears are yet too numerous.”

By the early 1900s, however, the black bears in Western North Carolina began to disappear because of severe habitat loss from widespread deforestation and unregulated hunting and harvesting. Also, bears lost a major food source when the chestnut blight killed between 3 and 4 billion American chestnut trees during the first half of the 20th century. By 1970, bears were virtually exterminated in the Piedmont area of North Carolina with fewer than 1,500 bears left in the entire state, some surviving in the high elevation mountains of WNC and a few more in the coastal plains. In the early 1970s, efforts began at the State level to establish bear sanctuary systems (28 total) to protect the few remaining bears, especially female bears, which resulted in 800,000 acres being closed to hunting.

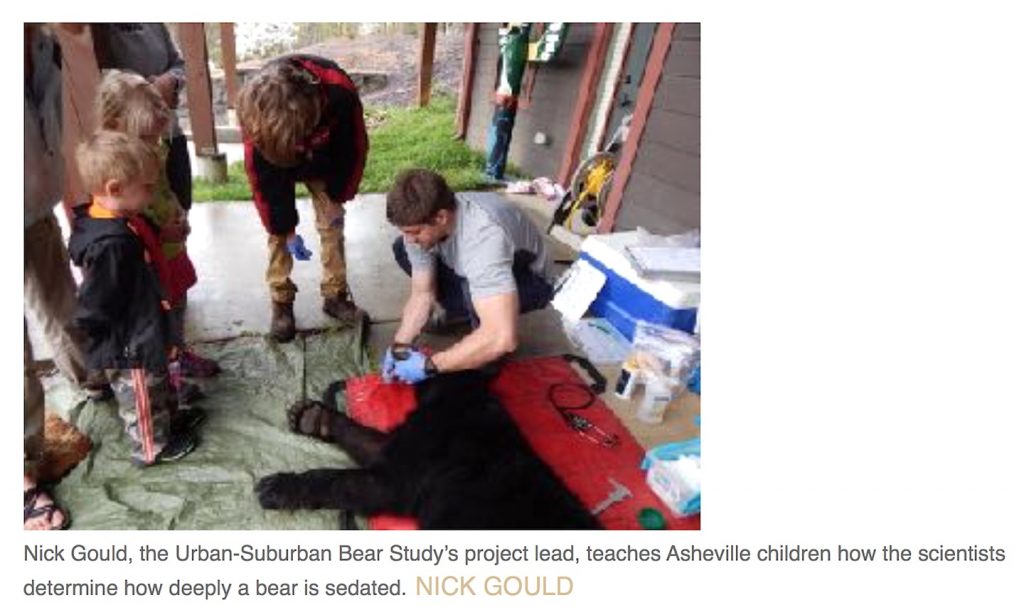

Despite continued hunting and both regulated and illegal harvesting, the statewide population of bears did gradually increase and is now between 15,000 to 20,000. This significant rebound in bear population is a tribute, not only to the establishment of sanctuary areas and other protective measures, but also to bears’ high intelligence and adaptability. But as the bear population increased in North Carolina, so did the human population which meant more human/bear encounters, especially in urban and suburban areas. For example, in 1993 the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission got 33 calls about human-bear encounters but in 2013, they got 569. To better understand this significant increase in human/bear encounters, the Wildlife Resources Commission collaborated with N.C. State University in 2014 to establish a five-year Urban/Suburban Bear Study.

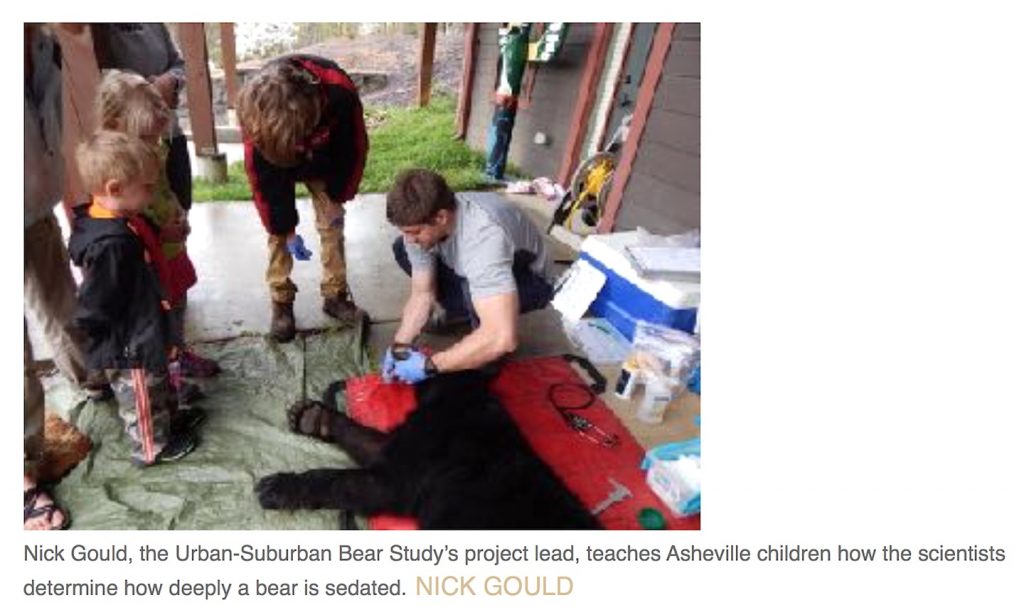

Asheville was chosen as the research study site because it had a high number of bears and good bear habitat both within and around the city; bear hunting was not permitted in the city limits; and people living in Asheville were fairly tolerant of bears. The main research strategy was to put GPS collars on several captured bears and track their movements within Asheville with the goals of developing a better understanding of city bears and developing strategies for optimal bear/human co-existence. Research for the study will continue through this month, April 2018. Then during the final year of the study, the Wildlife Resources Commission researchers will finish analyzing the data and use the study results to update their N.C. Black Bear Management Plan that spans 2012 -2022. The study is funded in part from the Federal tax on firearms and ammunition that directs revenue to wildlife research, wild game projects, and hunter education.

The six main research questions of the Urban/Suburban Bear Study include:

* How does bear behavior change as they move to urban/ suburban areas?

* Does the general population of urban bears start out in Asheville and move out or do they move in and generally end up staying? That is, are Asheville’s city bears a population source or a sink?

* How do bears travel through urban/suburban areas?

* How do bears select dens in urban/suburban areas?

* Do bears have greater fecundity and/or better health in urban/ suburban areas?

* How vulnerable are the urban/suburban bears to hunting when they travel outside the Asheville city limits?

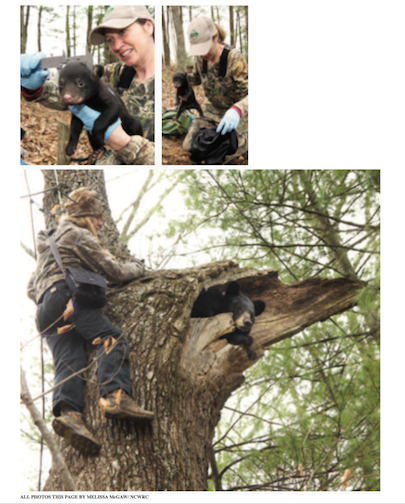

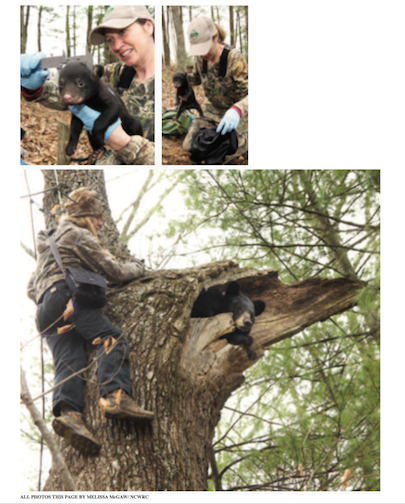

It is not easy to capture bears even though they are large animals because they are intelligent, wary, and elusive, so the researchers began by trapping bears that were showing up regularly on private property in the city. Also, the GPS tracking collars are quite heavy, so they can be attached to only about one-third of the captured bears. (Note: The collars are programmed to automatically unclasp and fall off bears after three years, or collars can be remotely unattached by the study biologists at any time.) With the attached GPS collars, the movements of the bears are tracked with updates every 15 minutes effectively mapping where and how far they travel; where and how long they den; their territorial, mating and reproductive patterns; their interactions with people; and their survival rate and cause of death.

The researchers began the study by responding to calls from Asheville residents regarding black bear sightings on their property and asking residents if they could capture and use the captives in their bear study. Approximately 34% of these calls resulted in bears being collared with all of them weighing over 100 pounds. To date, they have captured 240 and recaptured 160 bears, all on private land within the Asheville area. There are 113 bears currently with collars and being tracked. The researchers mark all captured bears with tattoos and micro-chips so they can be identified as part of the study if they are found dead, for example, or captured for some reason on National Forest land or on other private land.

Asheville residents have been quite positive about both the ongoing research study and with living in close proximity to several bears, and the research results have been exceptionally useful, far exceeding study expectations. The research information compiled so far indicates that bears living in the Asheville area are heavier, healthier and more fit than bears living in the rural areas outside of Asheville. For example, the average weight of the male bears captured in Asheville is 572 pounds and that of females, 297 pounds, with both results at the higher end of overall average weight for all bears recorded in previous studies in Western North Carolina. Male yearling bears have been captured in Asheville that weigh more than 180 pounds each as well as female yearling bears that weigh more than 120 pounds each, compared to typical healthy yearling bears that weigh weigh on the average between 45 to 80 pounds each.

Also, most of the 2-year old captured Asheville bears successfully became pregnant earlier than is typical and had larger and healthier litters. Not only is the breeding age lower and the reproduction rate higher, the survival estimates for the adult captured bears living in Asheville are also significantly higher. For example, the survival rate of the bears (usually young males) that leave Asheville falls from about 67% to 23% indicating that the black bears that leave Asheville are more likely to die than to survive. More than half of these recorded mortalities for bears leaving Asheville are caused by being hit by vehicles with hunting, both legal and illegal, accounting for most of the rest. These results indicate that even though there is still fairly high bear mortality, Asheville is a source for the bear population of the surrounding area because of the higher reproduction rate of the city bears.

How do the bears behave as they adjust to life in Asheville? The main reason the Asheville/Buncombe area was chosen as a study site is that bears are everywhere throughout the region with many human/bear interactions being reported every year. Once the GPS collars were attached to study bears, the maps of the bears’ movements correspond almost exactly to a map of Asheville and shows them crisscrossing everywhere within the area. Even with such close proximity to houses and people, injuries caused by bears are rare in Asheville just as they are throughout the WNC area and in most regions of the country with significant black bear populations, occurring only about once every other year. Most of the human/bear encounters that result in injuries are from hunters trying to separate their dogs from bears or when a pet owner tries to rescue a dog that was attacking a bear. Even though they are large animals, bears are generally wary and elusive and not hostile or aggressive toward people or other animals.

The research study results indicate that the main reason that Asheville residents are surprisingly tolerant of bears is because the bears mostly ignore humans and try to avoid them. The researchers promote, and most people in Asheville neighborhoods follow, the recommendations of BearWise.org, a regional program to encourage community initiatives to keep bears wild instead of increasingly attracted to human “handouts”. BearWise recommendations include, for example, never approaching, surprising, or feeding bears; removing bird feeders or keeping them out of the reach of bears; and keeping garbage cans stationary with their lids bolted shut.

Bears have high nutritional needs, requiring several pounds of food a day — they are largely vegetarian eaters and generally spend their time wandering around eating an omnivorous diet mainly consisting of plants, roots, twigs, buds, nuts, berries and other fruits, insects, worms and larvae. They are quite adaptable and opportunistic generally eating whatever is available including small mammals such as mice and moles, honey from bee hives, and human food and garbage. The results of the study indicate that city bears are not always territorial and that individual bears vary significantly in their travel around Asheville. Some stay in one area almost exclusively while other collared bears travel widely for miles almost daily, moving in and out of various areas. One supposition about why urban bears are healthier is that they are not as wary and fearful about being hunted or harried, so they can spend more time wandering around eating.

Another adaptable quality of bears is that they essentially go dormant in the winter by ramping down their metabolism and entering a state of torpor or hibernation during which they don’t eat, drink, urinate, or defecate and typically lose 15 to 25% of their body weight. It was generally assumed that most bears enter dens during the winter, but the data from the research study indicates that the collared bears in the Asheville area don’t always den as they do in in other regions. Sometimes they just hibernate by huddling together in a safe place to wait out the cold weather, although pregnant females will usually enter a den to hibernate, ideally a tall, hollow tree. Some of the collared bears have hibernated under porches, sometimes with the residents not even realizing they were there, or in a heap with other bears under trees. Some bears, especially females with cubs, spend the winter hunkered down in areas where no one is around for example, within the small wooded tracts of land between the roads of the interstate freeway system.

Photo by: Barbara Harrison

The results of the Urban/Suburban Bear study indicate that there is still much to learn about black bears in general and specifically about humans and bears living in close proximity with one important question being: How

many bears can the city hold? The answer seems to be as many as residents will accept and that the area’s habitat can support. I attended an excellent BRNN presentation in February 2018 about the Urban/Suburban bear study and when the presenter asked for questions at the end, one person asked why the research biologists didn’t just capture Asheville’s bears and remove them from the city to the “places where they belong” because they are a threat to the city’s residents. The researcher, Jennifer Strules, explained that although of course they can be dangerous, black bears are rarely ever a threat to people, who are much more likely to be injured by cars and other vehicles, guns and even dogs, and that bears do “belong” where they are just as we humans do. She concluded that hopefully, the information from the study will provide both better understanding about the biology and behavior of the city’s bears and science-based strategies to help bears and humans successfully coexist wherever they live together.